Automated tests can typically be run by running a script manually, or using a helper from a testing framework, often called a test runner, to find and run tests. You might not always want to have to run your scripts manually, though. There are a number of ways to run your tests that can provide feedback and confidence at different points during the development lifecycle.

Prerequisite script

Web projects usually have a configuration file—their package.json file—that is

set up by npm, pnpm, Bun or similar. This configuration file contains your

project's dependencies and other information, as well as helper scripts. These

helper scripts might include how to build, run or test your project.

Inside package.json, you'll need to add a script called test that describes

how to run your tests. This is important because, when using npm or a similar

tool, the "test" script has special meaning.

This script can just point to a single file that throws an exception—

something like node tests.js—but we recommend using it to point to an

established test runner.

If you're using Vitest as your test runner, your

package.json file will look like the following:

{

"name": "example-project",

"scripts": {

"start": "node server.js",

"test": "vitest --run"

}

}

Running npm test with this file runs Vitest's default set of tests once. In

Vitest, the default is to find all files that end with ".test.js" or

similar and run them. Depending on your

chosen test runner, the command may be slightly different.

We've chosen to use Vitest, an increasingly popular test framework, for examples throughout this course. You can read more about this decision in Vitest as a test runner. However, it's important to remember that test frameworks and runners—even across languages—tend to have a common vernacular.

Manual test invocation

Manually triggering your automated tests (such as using npm test in the

previous example) can be practical while you're actively working on a codebase.

Writing tests for a feature while developing that feature can help you get a

sense of the way the feature should work—this touches on the concept of

test-driven development (TDD).

Test runners will typically have a short command you can invoke to run some or

all of your tests, and possibly a watcher mode that reruns tests as you save

them. These are all helpful options while developing a new feature, and they're

designed to make it easy to write either a new feature, its tests, or both, all

with rapid feedback. Vitest, for example, operates in watcher mode by default:

the vitest command will watch for changes and re-run any tests it finds. We

recommend leaving this open in another window while you write tests, so you can

get rapid feedback about your tests as you develop them.

Some runners also allow you to mark tests as only in your code. If your code

includes only tests, then only these tests will trigger when you run testing,

making test development quicker and easier to troubleshoot. Even if all your

tests complete quickly, using only can reduce your overhead and remove the

distraction of running tests unrelated to the feature or test you're working on.

For small projects, especially projects with only one developer, you might also want to develop a habit of running your codebase's entire test suite regularly. This is especially helpful if your tests are small and complete quickly (in no more than a few seconds for all of your tests) so you can make sure everything is working before you move on.

Run tests as part of presubmit or review

Many projects choose to confirm that a codebase is functioning correctly when

code is to be merged back into its main branch. If you're new to testing, but

have contributed to open source projects in the past, you've probably noticed

part of the pull request (PR) process confirms that all the project's tests

pass, meaning that your exciting new contribution hasn't negatively affected the

existing project.

If you run your tests locally, your project's online repository (for example, GitHub or another code hosting service) won't know that your tests are passing, so running tests as a presubmit task makes it clear to all contributors that everything is working.

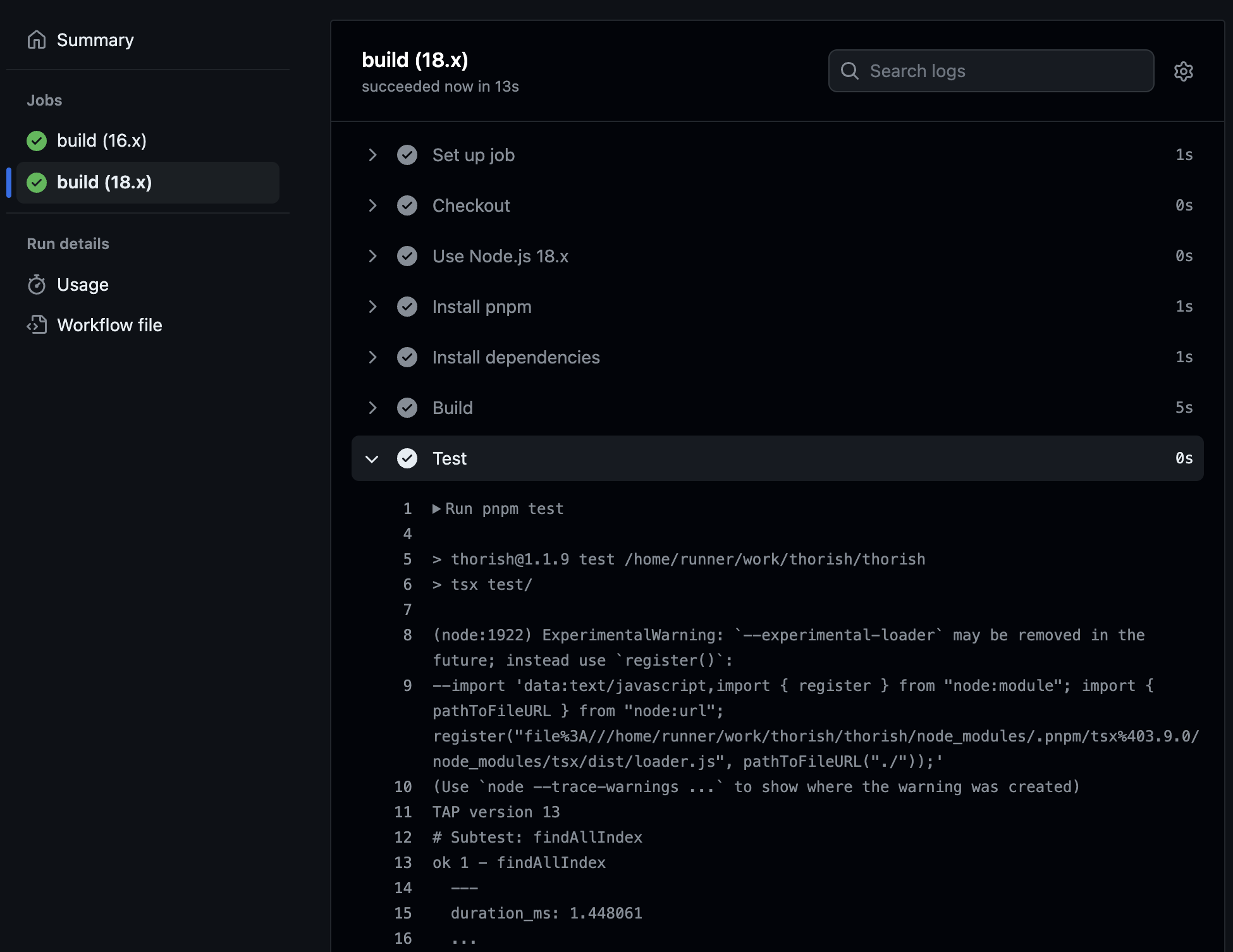

GitHub, for example, refers to these as "status checks" that you can add through

GitHub Actions. GitHub Actions are

fundamentally a kind of test: each step must succeed (not fail, or throw an

Error) for the action to pass. You can apply Actions to all PRs for a project,

and a project can require that Actions pass before you contribute code. GitHub's

default Node.js action runs npm test as one of its steps.

This approach to testing attempts to make sure your codebase is always "green" by not accepting code that doesn't successfully run its tests.

Run tests as part of Continuous Integration

Once your green PR has been accepted, most codebases run tests again based on

your project's main branch, rather than the prior PR. This might happen

immediately, or on a regular basis (for example, hourly or nightly). These

results are often shown as part of a Continuous Integration (CI) dashboard that

shows overall project health.

This CI step might seem redundant, especially for projects with small codebases— tests passed during review, so they should pass once a change is in. However, this isn't always true! Your tests might fail suddenly, even after successfully producing green results. Some reasons for this include:

- Several changes were accepted "at once", sometimes known as a race condition, and they affect each other in subtle, untested ways.

- Your tests aren't reproducible, or they test "flaky" code—they can both pass

and fail with no code changes.

- This might occur if you depend on systems external to your codebase. For a

proxy, imagine testing if

Math.random() > 0.05—this would randomly fail 5% of the time.

- This might occur if you depend on systems external to your codebase. For a

proxy, imagine testing if

- Some tests are too costly or expensive to run on every PR, such as end-to-end tests (more on this in types of automated testing), and they can break over time without always alerting.

None of these issues are impossible to overcome, but it's worth realizing that testing, and software development in general, is never going to be an exact science.

An interlude on rolling back

When tests are run as part of continuous integration, and even when tests are run as part of a status check, it's possible that the build ends up in a "red" state, or another state that means tests are failing. As mentioned previously, this can happen for a number of reasons, including race conditions on test submission, or flaky tests.

For smaller projects, your instinct might be to treat it as a crisis! Stop everything, roll back or revert the offending change, and get back to a known good state. This can be a valid approach, but it's important to remember that testing (and software in general!) is a means to an end, not an objective in itself. Your goal is probably to write software, not to make all the tests pass. Instead, you can roll forward by following up the breaking change with another change that fixes the failed tests.

On the other hand, you might have seen, or worked on, large projects that exist in a perpetually broken state. Or worse, the large project has a flaky test that breaks often enough to cause alarm fatigue in developers. This is often an existential problem for leaders to solve: these tests might even be turned off because they're seen as "getting in the way of development".

There's no quick fix for this, but it can help to become more confident writing tests (upskilling), and to reduce the scope of tests (simplification) so that failures can be more easily identified. An increased number of component tests or integration tests (more on types in Types of automated testing) can provide more confidence than one huge end-to-end test that's difficult to maintain and tries to do everything at once.

Resources

Check your understanding

What is the name of the special script that npm and similar programs look for while testing?