Large DOM sizes have more of an effect on interactivity than you might think. This guide explains why, and what you can do.

There's no way around it: when you build a web page, that page is going to have a Document Object Model (DOM). The DOM represents the structure of your page's HTML, and gives JavaScript and CSS access to a page's structure and contents.

The problem, however, is that the size of the DOM affects a browser's ability to render a page quickly and efficiently. Generally speaking, the larger a DOM is, the more expensive it is to initially render that page and update its rendering later on in the page lifecycle.

This becomes problematic in pages with very large DOMs when interactions that modify or update the DOM trigger expensive layout work that affects the ability of the page to respond quickly. Expensive layout work can affect a page's Interaction to Next Paint (INP); If you want a page to respond quickly to user interactions, it's important to ensure your DOM sizes are only as large as necessary.

When is a page's DOM too large?

According to Lighthouse, a page's DOM size is excessive when it exceeds 1,400 nodes. Lighthouse will begin to throw warnings when a page's DOM exceeds 800 nodes. Take the following HTML for example:

<ul>

<li>List item one.</li>

<li>List item two.</li>

<li>List item three.</li>

</ul>

In the above code, there are four DOM elements: the <ul> element, and its three <li> child elements. Your web page will almost certainly have many more nodes than this, so it's important to understand what you can do to keep DOM sizes in check—as well as other strategies to optimize the rendering work once you've gotten a page's DOM as small as it can be.

How do large DOMs affect page performance?

Large DOMs affect page performance in a few ways:

- During the page's initial render. When CSS is applied to a page, a structure similar to the DOM known as the CSS Object Model (CSSOM) is created. As CSS selectors increase in specificity, the CSSOM becomes more complex, and more time is needed to run the necessary layout, styling, compositing, and paint work necessary to draw the web page to the screen. This added work increases interaction latency for interactions that occur early on during page load.

- When interactions modify the DOM, either through element insertion or deletion, or by modifying DOM contents and styles, the work necessary to render that update can result in very costly layout, styling, compositing, and paint work. As is the case with the page's initial render, an increase in CSS selector specificity can add to rendering work when HTML elements are inserted into the DOM as the result of an interaction.

- When JavaScript queries the DOM, references to DOM elements are stored in memory. For example, if you call

document.querySelectorAllto select all<div>elements on a page, the memory cost could be considerable if the result returns a large number of DOM elements.

All of these can affect interactivity, but the second item in the list above is of particular importance. If an interaction results in a change to the DOM, it can kick off a lot of work that can contribute to a poor INP on a page.

How do I measure DOM size?

You can measure DOM size in a couple of ways. The first method uses Lighthouse. When you run an audit, statistics on the current page's DOM will be in the "Avoid an excessive DOM size" audit under the "Diagnostics" heading. In this section, you can see the total number of DOM elements, the DOM element containing the most child elements, as well as the deepest DOM element.

A simpler method involves using the JavaScript console in the developer tools in any major browser. To get the total number of HTML elements in the DOM, you can use the following code in the console after the page has loaded:

document.querySelectorAll('*').length;

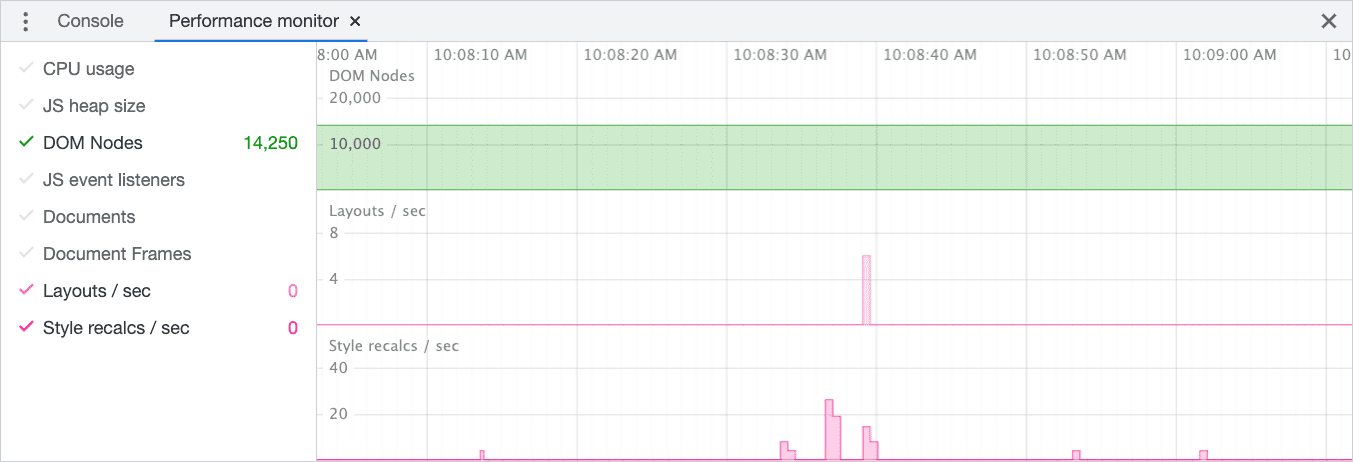

If you want to see the DOM size update in realtime, you can also use the performance monitor tool. Using this tool, you can correlate layout and styling operations (and other performance aspects) along with the current DOM size.

If the DOM's size is approaching Lighthouse DOM size's warning threshold—or fails altogether—the next step is to figure out how to reduce the DOM's size to improve your page's ability to respond to user interactions so that your website's INP can improve.

How can I measure the number of DOM elements affected by an interaction?

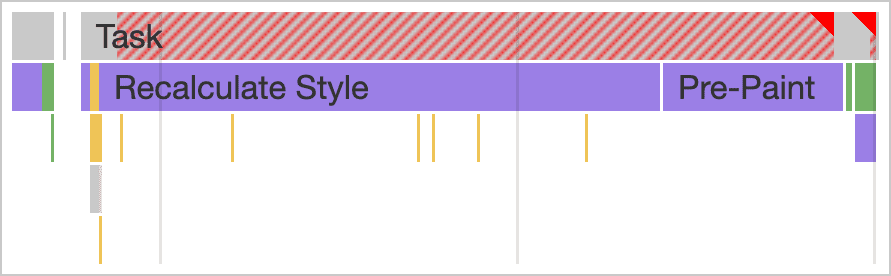

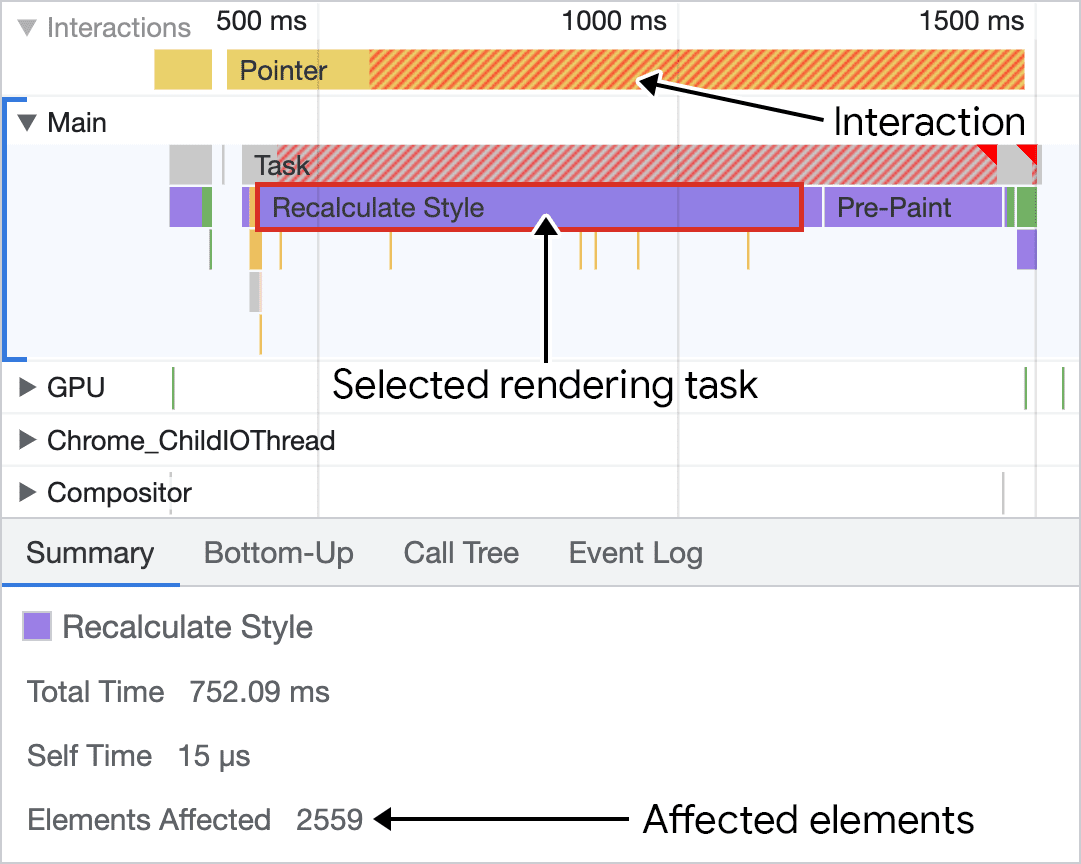

If you're profiling a slow interaction in the lab that you suspect might have something to do with the size of the page's DOM, you can figure out how many DOM elements were affected by selecting any piece of activity in the profiler labeled "Recalculate Style" and observe the contextual data in the bottom panel.

In the above screenshot, observe that the style recalculation of the work—when selected—shows the number of affected elements. While the above screenshot shows an extreme case of the effect of DOM size on rendering work on a page with many DOM elements, this diagnostic info is useful in any case to determine if the size of the DOM is a limiting factor in how long it takes for the next frame to paint in response to an interaction.

How can I reduce DOM size?

Beyond auditing your website's HTML for unnecessary markup, the principal way to reduce DOM size is to reduce DOM depth. One signal that your DOM might be unnecessarily deep is if you're seeing markup that looks something like this in the Elements tab of your browser's developer tools:

<div>

<div>

<div>

<div>

<!-- Contents -->

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

When you see patterns like this, you can probably simplify them by flattening your DOM structure. Doing so will reduce the number of DOM elements, and likely give you an opportunity to simplify page styles.

DOM depth may also be a symptom of the frameworks you use. In particular, component-based frameworks—such as those that rely on JSX—require you to nest multiple components in a parent container.

However, many frameworks allow you to avoid nesting components by using what are known as fragments. Component-based frameworks that offer fragments as a feature include (but are not limited to) the following:

By using fragments in your framework of choice, you can reduce DOM depth. If you're concerned about the impact flattening DOM structure has on styling, you might benefit from using more modern (and faster) layout modes such as flexbox or grid.

Other strategies to consider

Even if you take pains to flatten your DOM tree and remove unnecessary HTML elements to keep your DOM as small as possible, it can still be quite large and kick off a lot of rendering work as it changes in response to user interactions. If you find yourself in this position, there are some other strategies you can consider to limit rendering work.

Consider an additive approach

You might be in a position where large parts of your page aren't initially visible to the user when it first renders. This could be an opportunity to lazy load HTML by omitting those parts of the DOM on startup, but add them in when the user interacts with the parts of the page that require the initially hidden aspects of the page.

This approach is useful both during the initial load and perhaps even afterwards. For the initial page load, you're taking on less rendering work up front, meaning that your initial HTML payload will be lighter, and will render more quickly. This will give interactions during that crucial period more opportunities to run with less competition for the main thread's attention.

If you have many parts of the page that are initially hidden on load, it could also speed up other interactions that trigger re-rendering work. However, as other interactions add more to the DOM, rendering work will increase as the DOM grows throughout the page lifecycle.

Adding to the DOM over time can be tricky, and it has its own tradeoffs. If you're going this route, you're likely making network requests to get data to populate the HTML you intend to add to the page in response to a user interaction. While in-flight network requests are not counted towards INP, it can increase perceived latency. If possible, show a loading spinner or other indicator that data is being fetched so that users understand that something is happening.

Limit CSS selector complexity

When the browser parses selectors in your CSS, it has to traverse the DOM tree to understand how—and if—those selectors apply to the current layout. The more complex these selectors are, the more work the browser has to do in order to perform both the initial rendering of the page, as well as increased style recalculations and layout work if the page changes as the result of an interaction.

Use the content-visibility property

CSS offers the content-visibility property, which is effectively a way to lazily render off-screen DOM elements. As the elements approach the viewport, they're rendered on demand. The benefits of content-visibility don't just cut out a significant amount of rendering work on the initial page render, but also skip rendering work for offscreen elements when the page DOM is changed as the result of a user interaction.

Conclusion

Reducing your DOM size to only what is strictly necessary is a good way to optimize your website's INP. By doing so, you can reduce the amount of time it takes for the browser to perform layout and rendering work when the DOM is updated. Even if you can't meaningfully reduce DOM size, there are some techniques you can use to isolate rendering work to a DOM subtree, such as CSS containment and the content-visibility CSS property.

However you go about it, creating an environment where rendering work is minimized—as well as reducing the amount of rendering work your page does in response to interactions—the result will be that your website will feel more responsive to users when they interact with them. That means you'll have a lower INP for your website, and that translates to a better user experience.