What is a third-party?

It's rather rare that a website is wholly self-contained. The HTTP Web Almanac shows that most websites—around 95%—contain some third-party content.

The Almanac defines third-party content as something hosted on a shared and public origin, which is widely used by a variety of sites and uninfluenced by an individual site owner. These might be images or other media such as video, fonts, or scripts. Images and scripts account for more than everything else added together. Third-party content isn't essential for developing a site, but it might as well be; you will almost certainly be using something loaded from a public shared server, whether web fonts, embedded iframes of videos, adverts, or JavaScript libraries. For example, you may be using web fonts served from Google Fonts, or measuring analytics with Google Analytics; you may have added Like buttons or Sign In With buttons from social networks; you may be embedding maps or video, or handling shopping purchases via third-party services; you may be tracking errors and logging for your own development teams via third-party monitoring tools.

For privacy purposes, it is useful to consider a slightly different and less broad definition: a third-party resource, and in particular a third-party script, is served from a shared and public origin and widely used as illustrated, but is also authored by someone other than the site owner. The aspect of third-party authorship is what's key when considering how to protect your users' privacy from others. This will lead you to consider what risks are present, and then decide how or whether to use a third-party resource based on those risks. As already discussed, these things will help you to understand the context and therefore to understand which trade-offs you need to make, and what they mean.

This isn't quite what's meant when discussing "third-party resources" in general: the distinction between first-party and third-party is really one about the context in which something is used. A script loaded from another website is a third-party resource, and the HTTP request which loads the script may include cookies, but those cookies aren't really "third-party cookies"; they're just cookies, and whether they're "third-party" or "first-party" depends on whether the script is being loaded on a page on your site or a page on the script owner's site.

Why do we use third-party resources?

Third-parties are a great way to add functionality to your site. That may be features that are exposed to users, or invisible developer functions such as error tracking, but they reduce your development load, and the scripts themselves are maintained by someone else: the development team of the service you're including. This all works because of the composability of the web: being able to put parts together to form a whole that is greater than their sum.

The HTTP Archive's Web Almanac gives a nice description:

Third parties provide a never-ending collection of images, videos, fonts, tools, libraries, widgets, trackers, ads, and anything else you can imagine embedding into our web pages. This enables even the most non-technical to be able to create and publish content to the web. Without third parties, the web would likely be a very boring, text-based, academic medium instead of the rich, immersive, complex platform that is so integral to the lives of many of us today.

What can third-party resources do?

Accessing some information

When you use a third-party resource on your website, regardless of what it is, some information is passed to that third party. For example, if you include an image from another site, the HTTP request that the user's browser makes will pass along a Referer header with your page's URL, as well as the user's IP address.

Cross-site tracking

Continuing with that same example—when the image loads from the third-party site, it can include a cookie, and that cookie will be sent back to the third-party when the user next requests that image. This means that the third party can know that their service is being used on your site, and it can send back a cookie, potentially with a unique ID for that user. This means that the next time the user visits your site, or any other site which includes a resource from that third party, that unique ID cookie will be sent again. This allows the third party to build up a log of where that user visits: your site, other sites that use the same third-party resource, all over the web.

This is cross-site tracking: allowing a third party to collect a log of a user's activity on many websites, as long as those websites all use a resource coming from the same third party. That might be a font, an image, or a stylesheet—all static resources. It also might be a dynamic resource: a piece of script, a social media button, an advert. Included script can gather even more information, because it is dynamic: it can inspect the user's browser and environment and pass that data back to its originator. Any script can do this to some extent, as can dynamic resources that don't present as a script, such as a social media embed or an ad or a share button. If you look at the details of a cookie banner on popular websites you can see a list of the organizations that may add a tracking cookie to your users to build up a picture of their activities to create a profile of that user. There can be hundreds of them. If a third party offers a service for free, one way that this can be economically viable for them to do is because they collect and then monetise this data.

A useful guide to the types of privacy issues from which a browser should protect its users is the Target Privacy Threat Model. This is a document still under discussion at the time of writing, but it gives some high-level classifications of the sorts of privacy threats that exist. The risks from third-party resources are primarily "unwanted cross-site recognition", where a website can identify the same user across multiple sites, and "sensitive information disclosure", where a site can collect information a user considers sensitive.

This is a key distinction: unwanted cross-site recognition is bad even if the third party isn't gathering additional sensitive information from it, because it takes away a user's control over their identity. Getting access to a user's referrer and IP address and cookies is an unwanted disclosure in itself. Using third-party resources comes along with a planning component of how you'll use them in a privacy-preserving way. Some of that work is in your remit as the site developer, and some is done by the browser in its role as the user agent; that is, the agent working on behalf of the user to avoid sensitive information disclosure and unwanted cross-site recognition where possible. Below we'll look in more detail at mitigations and approaches on a browser level and a site development level.

Server-side third-party code

Our earlier definition of a third party deliberately altered the HTTP Almanac's rather client-side approach (as is appropriate for their report!), to include third-party authorship, because from a privacy perspective, a third party is anyone who knows anything about your users who isn't you.

This does include third parties who provide services that you use on the server, as well as the client. From a privacy standpoint, a third-party library (such as something included from NPM or Composer or NuGet) is also important to understand. Do your dependencies pass data outside your borders? If you pass data to a logging service or a remotely hosted database, if libraries you include also "phone home" to their authors, then these may be in a position to violate your users' privacy and therefore they need to be audited. A server-based third party usually has to be handed the user data by you, which means that the data it is exposed to is more under your control. By contrast, a client-based third party—a script or HTTP resource included on your website and fetched by the user's browser—can collect some data directly from the user without that process of collection being mediated by you. Most of this module will be concerned with how to identify those client-side third parties you've elected to include and expose your users to, exactly because there is less mediation possible by you. But it is worth considering securing your server-side code so that you understand outbound communications from it and can log or block any that are unexpected. Details on how exactly to do this are outside our scope here (and very dependent on your server setup) but this is another part of your security and privacy stance.

Why do you need to be careful with third parties?

Third-party scripts and features are really important, and our goal as web developers should be to integrate such things, not to turn away from them! But there are potential problems. Third-party content may create performance issues and can also create security issues because you're bringing in an external service inside your trust boundary. But third-party content can also create privacy issues!

When we're talking about third-party resources on the web, it's useful to think of security issues being (among other things) where a third party can steal data from your company, and to contrast that with privacy issues, which are (among other things) where a third party that you included steals or obtains access to your users' data without you (or them) consenting.

An example of a security issue is where "web skimmers" steal credit card information-–a third-party resource which is included on a page into which a user enters credit card details can, potentially, steal those credit card details and send them off to the malicious third party. Those who create these skimmer scripts are very creative in working out places to hide them. One summary describes how skimmer scripts have been hidden in third-party content such as those images used for site logos, favicons, and social media networks, popular libraries such as jQuery, Modernizr, and Google Tag Manager, site widgets such as live chat windows, and CSS files.

Privacy issues are a little different. These third parties are part of your offering; to maintain your users' trust in you, you need to be confident that your users can trust them. If a third party that you use gathers data about your users and then misuses it, or makes it difficult to delete or discover, or suffers a data breach, or violates your users' expectations, then your users will likely perceive that as a breakdown in their trust of your service, not simply of the third party. It is your reputation and relationship on the line. This is why it's important to ask yourself: do you trust the third parties you're using on your site?

What are some examples of third parties?

We're discussing "third parties" generally, but there are actually different kinds, and they have access to different amounts of user data.

For example, adding an <img> element to your HTML, loaded from a different server, will give that server different information

about your users than adding an <iframe> might, or a <script> element. These are examples rather than a comprehensive list, but it's

useful to understand the distinctions between the different types of third-party items that your site can employ.

Requesting a cross-site resource

A cross-site resource is anything on your site which is loaded from a different site and isn't an <iframe> or a <script>. Examples

include <img>, <audio>, <video>, web fonts loaded by CSS, and WebGL textures. These are all loaded via an HTTP request, and as

described earlier, those HTTP requests will include any cookies previously set by the other site, the requesting user's IP address,

and the URL of the current page as the referrer. All third-party requests historically included this data by default, although

there are efforts to reduce or isolate the data passed to third parties by various browsers, as described in "Understanding

Third-Party Browser Protections" further on.

Embedding a cross-site iframe

A complete document embedded in your pages via an <iframe> can request additional access to browser APIs, in addition to the trifecta

of cookies, IP address, and referrer. Exactly which APIs are available to <iframe>d pages and how they request access is browser-specific,

and is currently undergoing changes: see "Permissions Policy" below for current efforts to curtail or monitor API access in embedded

documents.

Executing cross-site JavaScript

Including a <script> element loads and runs cross-site JavaScript in the top-level context of your page. This means that the

script that runs has complete access to anything that your own first-party scripts do. Browser permissions still manage this data,

so requesting the user's location (for example) will still require user agreement. But any information present in the page or

available as JavaScript variables can be read by such a script, and this includes not just cookies that are passed to the third party

as part of the request, but also cookies that are intended for your site alone. Equally, a third-party script loaded onto your

page can make all the same HTTP requests that your own code does, meaning that it could make fetch() requests to your back-end APIs to get data.

Including third-party libraries in your dependencies

As described earlier, your server-side code will also likely include third-party dependencies, and these are indistinguishable from your own code in their power; code that you include from a GitHub repository or your programming language's library (npm, PyPI, composer, and so on) can read all the same data that your other code can.

Knowing your third parties

This, then, requires some understanding of your list of third-party suppliers, and what their privacy, data collection, and user experience stances and policies are. That understanding then becomes part of your series of trade-offs: how useful and important is the service, balanced against how intrusive, inconvenient, or disquieting their demands are on your users. Third-party content provides value by taking the heavy lifting from you as site owner and allows you to focus on your core competencies; and so there is value in making that trade-off and sacrificing some user comfort and privacy for a better user experience. It is important to not confuse user experience with developer experience, though: "it is easier for our dev team to build the service" is not a compelling story to users.

How you get that understanding is the process of audit.

Audit your third parties

Understanding what a third party does is the process of audit. You can do this both technically and non-technically, and for an individual third party and for your whole collection.

Run a non-technical audit

The first step is non-technical: read the privacy policies of your suppliers. If you include any third-party resources, check the privacy policies. They will be long and full of legal text, and some documents may use some of the approaches specifically warned against in earlier modules, such as overly general statements and without any indication of how or when collected data will be removed. It is important to realize that from a user perspective, all the data that is collected on your site, including by third parties, will be governed by these privacy policies. Even if you do everything correctly, when you are transparent about your goals and exceed your users' expectations of data privacy and sensitivity, users may hold you responsible for anything your chosen third parties do as well. If there is anything in their privacy policies which you would not wish to say in your own policies because it would decrease users' trust, then consider whether there is an alternative supplier.

This is something which can usefully go hand in hand with the technical audit discussed further on, as they inform one another. You should know the third-party resources that you're incorporating for business reasons (such as ad networks or embedded content) because there will be a business relationship in place. This is a good place to start a non-technical audit. The technical audit is also likely to identify third parties, especially those included for technical rather than business reasons (external components, analytics, utility libraries), and that list can join with the list of business-focused third parties. The goal here is for you as site owner to feel that you understand what the third parties you're adding to your site are doing, and for you as a business to be able to present your legal advisor with this inventory of third parties to make sure you are meeting any obligations required.

Run a technical audit

For a technical audit, it's important to use the resources in situ as part of the website; that is, don't load a dependency in a test harness and inspect it that way. Make sure you're seeing how your dependencies act as part of your actual website, deployed on the public internet rather than in a test or development mode. It is very instructive to view your own website as a new user. Open a browser in a clean new profile, so that you are not signed in and have no stored agreement, and try visiting your site.

Sign up on your own site for a new account, if you provide user accounts. Your design team will have orchestrated this new user

acquisition process from a UX perspective, but it can be illustrative to approach it from a privacy perspective. Don't simply click

"Accept" on the terms and conditions, or the cookie warning, or the privacy policy; set yourself the task of using your own service

without disclosing any personal information or having any tracking cookies, and see if you can do it and how hard it is to do it.

It can also be helpful to look in the browser developer tools to see which sites are being accessed and which data is passed to

those sites. Developer tools provide a list of separate HTTP requests (normally in a section called "Network"), and you can see

from here requests grouped by type (HTML, CSS, images, fonts, JavaScript, requests initiated by JavaScript). It's also possible

to add a new column to show the domain of each request, which will demonstrate how many different places are being contacted,

and there may be a "third-party requests" checkbox to show only third parties. (It can also be useful to use Content-Security-Policy

reporting to perform a continual audit, for which read further on.)

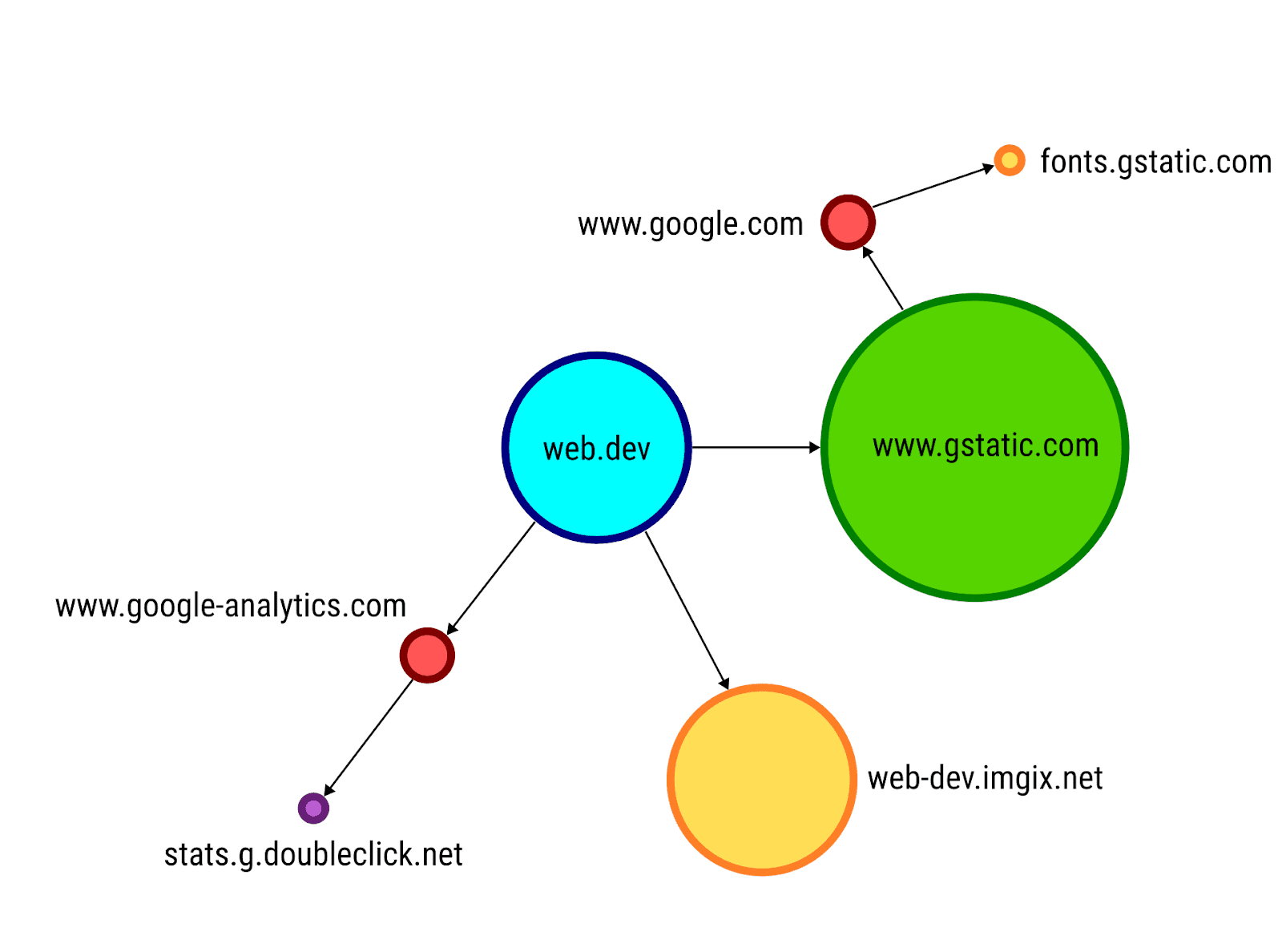

Simon Hearne's "Request Map Generator" tool can also be a helpful overview of all the subrequests that a publicly available page makes.

This is also the point at which you can include the business-focused third parties identified as part of the non-technical audit (that is: the list of companies that you have a financial relationship with in order to use their resources). The goal here is to match up the list of third parties you believe you're using (from financial and legal records) and the list you're actually using (by looking at which third-party HTTP requests your website makes). You should be able to identify for each business third party which technical outbound requests are made. If you cannot identify requests in the technical audit for a third party identified by business relationship, it's important to work out why and to have that guide your testing: perhaps that third-party resource is only loaded in a particular country, or on a particular device type, or for logged-in users. This will enlarge your list of site areas to audit and ensure that you're seeing all the outbound accesses. (Or possibly it will identify a third-party resource that you're paying for and not using, which always cheers up the finance department.)

Once you've narrowed down the list of requests to third parties that you would like to be part of the audit, clicking on an individual request will show all the details of it and, in particular, which data was passed to that request. It is also very common that a third-party request that your code initiates then goes on to initiate many other third-party requests. These additional third parties are also "imported" into your own privacy policy. This task is laborious but valuable, and it often can be inserted into existing analyses; your frontend development team should already be auditing requests for performance reasons (perhaps with the help of existing tools such as WebPageTest or Lighthouse), and incorporating a data and privacy audit into that process can make it easier.

Do

Open a browser with a clean new user profile, so that you are not signed in and have no stored agreement; then open the browser development tools Network panel to see all the outgoing requests. Add a new column to show the domain of each request, and check the "third-party requests" checkbox to show only third parties if present. Then:

- Visit your site.

- Sign up for a new account, if you provide user accounts.

- Try to delete your created account.

- Carry out a normal action or two on the site (exactly what this is will depend on what your site does, but pick common actions that most users perform).

- Carry out an action or two which you know involve third-party dependencies in particular. These might include sharing content to social media, beginning a checkout flow, or embedding content from another site.

When doing each of these tasks, make a record of resources requested from domains that are not yours, by looking at the Network panel as described. These are some of your third parties. A good way to do this is to use the browser network tools to capture the network request logs in a HAR file.

HAR files and capturing

An HAR file is a standardized JSON format of all network requests made by a page. To get an HAR file for a particular page, in:

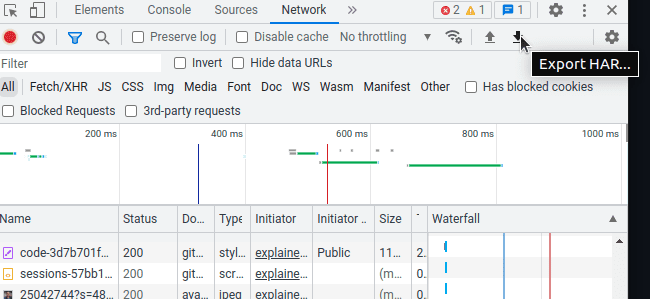

Chrome

Open the browser DevTools (Menu > More Tools > Developer Tools), go to the Network panel, load (or refresh) the page, and choose the downward arrow save symbol in the top right near to the No throttling dropdown menu.

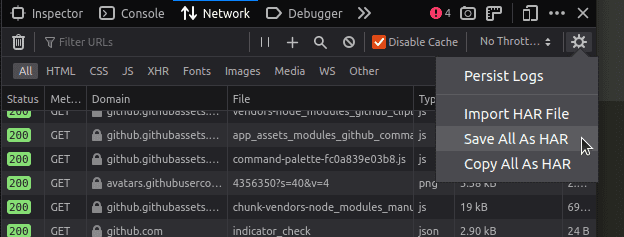

Firefox

Open the browser developer tools (Menu > More Tools > Web Developer Tools), go to the Network panel, load (or refresh) the page, and choose the cog symbol in the top right next to the throttling dropdown menu. From its menu, choose Save All As HAR**.

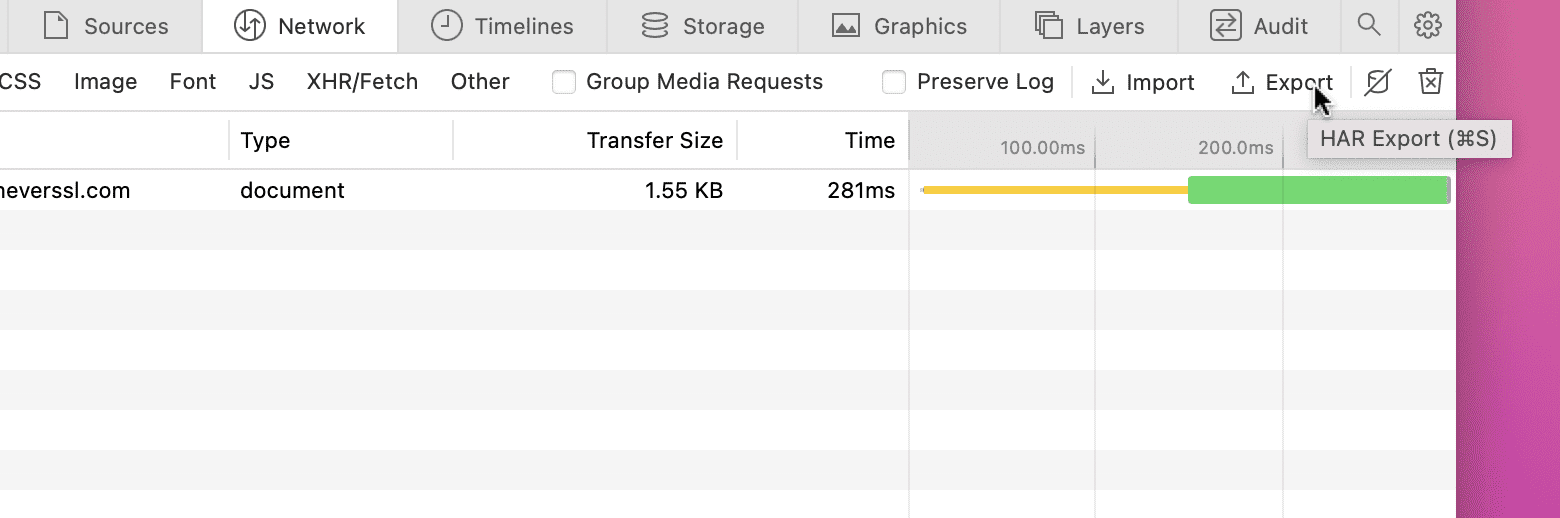

Safari

Open the browser developer tools (Menu > Develop > Show Web Inspector; if you don't have a Develop menu then enable it from Menu > Safari > Preferences > Advanced > Show Develop menu in menu bar), go to the Network panel, load (or refresh) the page, and choose Export in the top right (to the right of Preserve Log; you may need to enlarge the window).

For more detail, you can also record what is passed on to third parties (in the Request section), although this data is often obfuscated and not usefully interpretable.

Best practices when integrating third parties

You can set your own policies on which third parties your site uses: change which ad provider you use based on their practices, or how annoying or intrusive their cookies consent popup is, or whether you want to use social media buttons on your site or tracking links in your emails or utm_campaign links to track in Google Analytics in your tweets. One aspect to consider when developing a site is the privacy and security posture of your analytics service. Some analytics services explicitly trade on being privacy-protecting. Frequently, there are also ways to use a third-party script which adds privacy protection in itself: you are not the first team looking to improve their users' privacy and protect them from third-party data collection, and there may already be solutions. Finally, many third-party providers are more sensitive to data collection issues now than in the past, and there are often features or parameters you can add which enable a more user-protective mode. Here are some examples.

When adding a social media sharing button

Consider embedding HTML buttons directly: the site https://sharingbuttons.io/ has some well-designed examples. Or you could add plain HTML links. The trade-off here is that you lose the "share count" statistic and your ability to classify your customers in your Facebook analytics. This is an example of a trade-off between using a third party provider and receiving less analytics data.

More generally, when you're embedding an interactive widget of some kind from a third party, it's often possible to instead provide a link out to that third party. This does mean that your site doesn't have the inline experience, but it shifts the decision on sharing data with the third party from you to your user, who can choose to interact or not as they prefer.

For example, you might add links for Twitter and Facebook to share your service at mysite.example.com like this:

<a href="https://facebook.com/sharer/sharer.php?u=https%3A%2F%2Fmysite.example.com"

rel="noopener" aria-label="Share on Facebook" target="_blank" >Share on Facebook</a>

<a href="https://twitter.com/intent/tweet/?text=My%20cool%20service!&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmysite.example.com"

rel="noopener" aria-label="Share on Twitter" target="_blank">Share on Twitter</a>

Note that Facebook allows specifying a URL to share, and Twitter allows specifying a URL and some text.

When embedding a video

When you're embedding videos from video-hosting sites, look for privacy-preserving options in the embedding code.

For example, for YouTube, replace youtube.com in the embed URL with www.youtube-nocookie.com to avoid tracking cookies

being placed on users viewing the embedding page. You can also check "Enable privacy-enhanced mode" when generating the

Share/Embed link from YouTube itself. This is a good example of using a more user-protective mode provided by the third party.

(https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/171780 describes this in more detail,

and other embedding options for YouTube specifically.)

Other video sites have fewer options in this regard: TikTok, for example, doesn't have a way to embed video without tracking at the time of this writing. It is possible to host the videos yourself (this is using an alternative), but it can be a lot more work, especially to support many devices.

As with interactive widgets discussed earlier, it is often possible to replace an embedded video with a link to the providing website.

This is less interactive because the video won't play inline, but it leaves the choice of whether to watch with the user. This can be

used as an example of the "facade pattern", the name for dynamically replacing interactive content with something requiring a user

action to trigger it. An embedded TikTok video can be replaced with a plain link to the TikTok video page, but with a little more

work it is possible to retrieve and display a thumbnail for the video and make that a link. Even if the chosen video provider doesn't

support an easy way to embed videos without tracking, many video hosts support oEmbed, an API that, when given

a link to a video or embedded content, will return programmatic detail for it, including a thumbnail and title. TikTok supports oEmbed

(see https://developers.tiktok.com/doc/embed-videos for details), meaning that

you can (manually or programmatically) turn a link to a TikTok video https://www.tiktok.com/@scout2015/video/6718335390845095173 into JSON metadata about that video with

https://www.tiktok.com/oembed?url=https://www.tiktok.com/@scout2015/video/6718335390845095173, and therefore retrieve a thumbnail

to display. WordPress often uses this to request oEmbed' information for embedded content, for example. You can use this programmatically

to show a "facade" that looks interactive and switches to embed or link to an interactive video when the user chooses to click on it.

When embedding analytics scripts

Analytics is designed to collect info about your users so it can be analyzed: this is what it's for. Analytics systems are essentially services to collect and display data about accesses and users, which is done on a third-party server such as Google Analytics for ease of implementation. There are also self-hosted analytics systems such as https://matomo.org/, although this is more work than using a third-party solution for this. Running such a system on your own infrastructure does help you to reduce data collection, though, because it does not leave your own ecosystem. On the other hand, managing that data, removing it, and setting policies for it becomes your responsibility. Much of the concern with cross-site tracking comes about when it's done surreptitiously and secretively, or as a side-effect of using a service which need not contain data gathering at all. Analytics software is overtly designed to collect data in order to inform the site owners about their users.

Historically, there has been an approach of gathering all the data you can about everything, like a giant fishing net, and then analyzing it later for interesting patterns. This mindset has, in large part, created the sense of unease and disquiet about data collection that was discussed in part 1 of this course. Now, many sites first work out which questions to ask and then gather specific and limited data to answer those questions.

If some third-party service is used by your site and by other sites, and it works by you including their JavaScript into your site, and it sets cookies for each user, then it's important to consider that they could be doing unwanted cross-site recognition; that is, tracking your users across sites. Some may and some may not, but the privacy-protecting stance here is to assume that such a third-party service is in fact doing cross-site tracking unless you have a good reason to think or know otherwise. This is not in itself a reason to avoid such services, but it is something to consider in your assessment of the trade-offs of using them.

The trade-off in analytics used to be solely to choose whether to use it or not: gather all data and compromise privacy in exchange for insights and planning, or give up insights entirely. However, this is no longer the case, and there is often now a middle ground to be found between these two extremes. Check your analytics provider for configuration options to limit the data collected and reduce the amount and duration of its storage. Since you have the records from the technical audit described earlier, you can re-run the relevant sections of that audit to confirm that changing these configurations does actually reduce the amount of data collected. If you're making this transition on an existing site, then this can give you some quantifiable measure that can be written about for your users. For example, Google Analytics has a number of opt-in (therefore off by default) privacy features, many of which may be helpful for complying with local data protection laws. Some options to consider when setting up Google Analytics include setting the retention period on collected data (Admin > Tracking Info > Data Retention) lower than the 26-month default, and enabling some of the more technical solutions such as partial IP anonymization (see https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/9019185 for more detail).

Using third parties in a privacy-preserving way

Thus far, we've discussed how to protect your users from third parties during the design phase of your application, while you're planning what that application will do. Deciding to not use a particular third party at all is part of this planning, and auditing your uses also falls into this category: it's about making decisions about your privacy stance. However, these decisions are inherently not very granular; choosing to use a particular third party or choosing not to is not a nuanced decision. It is much more likely that you will want something in between: to need or plan to use a particular third-party offering but mitigate any privacy-violating tendencies (whether deliberate or accidental). This is the task of protecting users at "build time": adding safeguards to reduce harm that you did not anticipate. All these are new HTTP headers that you can provide when serving pages and which will hint or command the user agent to take certain privacy or security stances.

Referrer-Policy

Do

Set a policy of strict-origin-when-cross-origin or noreferrer to prevent other sites from receiving a Referer header

when you link to them or when they're loaded as subresources by a page:

index.html:

<meta name="referrer" content="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" />

Or server-side, for example in Express:

const helmet = require('helmet');

app.use(helmet.referrerPolicy({policy: 'strict-origin-when-cross-origin'}));

If need be, set a laxer policy on specific elements or requests.

Why this protects user privacy

By default, each HTTP request the browser makes passes on a Referer header which contains the URL of the page initiating the request,

whether a link, an embedded image, or script. This can be a privacy issue because URLs can contain private information, and those URLs

being available to third parties passes that private information to them. Web.dev lists some examples

of URLs containing private data—knowing that a user came to your site from https://social.example.com/user/me@example.com tells you who that user is,

which is a definite leak. But even a URL which does not itself expose private information does expose that this particular user (who you may know,

if they're logged in) came here from another site and this therefore reveals that this user visited that other site. This is in itself exposure of

information that you maybe should not know about your user's browsing history.

Providing a Referrer-Policy header (with correct spelling!) lets you alter this, so that some or none of the referring URL is passed on.

MDN lists the full details but most browsers have

now adopted an assumed value of strict-origin-when-cross-origin by default, meaning that the referrer URL is now passed to third

parties as an origin only (https://web.dev rather than https://web.dev/learn/privacy). This is a useful privacy protection without

you having to do anything. But you can tighten this up further by specifying Referrer-Policy: same-origin to avoid passing any

referrer information at all to third parties (or Referrer-Policy: no-referrer to avoid passing to anyone including your own origin).

(This is a nice example of the privacy-versus-utility balance; the new default is much more privacy-preserving than before, but it

still gives high level information to third parties of your choice, such as your analytics provider.)

It's also useful to explicitly specify this header because then you know exactly what the policy is, rather than relying on the browser defaults.

If you aren't able to set headers, then it's possible to set a referrer policy for a whole HTML page using a meta element in the <head>:

<meta name="referrer" content="same-origin">; and if concerned about specific third parties, it's also possible to set a referrerpolicy

attribute on individual elements such as <script>, <a>, or <iframe>: <script src="https://thirdparty.example.com/data.js" referrerpolicy="no-referrer">

Content-Security-Policy

The Content-Security-Policy header, often referred to as "CSP", dictates where external resources can be loaded from.

It is primarily used for security purposes, by preventing cross-site scripting attacks and script injection, but when used

alongside your regular audits it can also limit where your chosen third parties can pass data to.

This is potentially a less-than-great user experience; if one of your third-party scripts starts loading a dependency from an origin not on your list, then that request will be blocked, the script will fail, and your application may fail with it (or at least be reduced to its JavaScript-failing fallback version). This is useful when CSP is implemented for security, which is its normal purpose: protecting against cross-site scripting issues (and to do this, use a strict CSP). Once you know all the inline scripts that your page uses, you can make a list of them, calculate a hash value or add a random value (called a "nonce") for each, and then add the list of hashes to your Content Security Policy. This will prevent any script that isn't on the list from being loaded. This needs to be baked into the production process for the site: scripts in your pages need to include the nonce or to have a hash calculated as part of the build. See the article on strict-csp for all the details.

Fortunately, browsers support a related header, Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only. If this header is provided, requests

that violate the supplied policy will not be blocked, but a JSON report will be sent to a supplied URL. Such a header might

look like this:

Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only: script-src 3p.example.com; report-uri https://example.com/report/,

and if the browser loads a script from anywhere other than 3p.example.com, that request will succeed but a report will

be sent to the supplied report-uri. Normally this is used to experiment with a policy before implementing it, but a useful

idea here is to use this as a way of conducting an "ongoing audit". As well as your regular audit described earlier, you

can turn on CSP reporting to see if any unexpected domains appear, which could mean that your third-party resources are loading

third-party resources of their own and which you need to consider and evaluate. (It may also be a sign of some cross-site

scripting exploits having slipped past your security boundary, of course, which it is also important to know about!)

Content-Security-Policy is a complex and fiddly API to use. This is known, and there is work going on to build the "next generation" of CSP

which will meet the same goals but not be quite as complicated to use.This isn't ready yet, but if you'd like to see where this is heading

(or to get involved and help in its design!) then check out https://github.com/WICG/csp-next for details.

Do

Add this HTTP header to pages served: Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only: default-src 'self'; report-uri https://a-url-you-control.

When JSON is posted to that URL, store it. Review that stored data to get a collection of the third-party domains that your website requests when visited by others.

Update the Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only header to list the domains you expect, in order to see when that list changes:

Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only: default-src 'self' https://expected1.example.com https://expected2.example.com ; report-uri https://a-url-you-control

Why

This forms part of your technical audit, in an ongoing fashion. The initial technical audit you performed will give you a

list of third parties that your site shares or passes user data to. This header will then cause page requests to report

back which third parties are now being contacted, and you can track changes over time. This not only alerts you to changes

made by your existing third parties, but will also flag newly added third parties which weren't added to the technical audit.

It's important to update the header to stop reporting about domains you expect, but it's also important to repeat the manual

technical audit from time to time (because the Content-Security-Policy approach does not flag what data is passed, only

that a request has been made.)

Note that it does not need to be added to the pages served every time, or every page. Tune down how many page responses receive the header so that you receive a representative sample of reports that aren't overwhelming in quantity.

Permissions policy

The Permissions-Policy header (which was introduced under the name Feature-Policy) is similar in concept to Content-Security-Policy,

but it restricts access to powerful browser features. For example, it’s possible to restrict use of device hardware such as the accelerometer,

camera, or USB devices, or to restrict non-hardware features such as permission to go fullscreen or use synchronous XMLHTTPRequest.

These restrictions can be applied to a top-level page (to avoid loaded scripts from attempting to use these features) or to

subframed pages loaded in via an iframe. This restriction of API usage isn’t really about browser fingerprinting; it's about disallowing third-parties from doing intrusive things (such as using powerful APIs, popping up

permissions windows, etc). This is defined by the Target Privacy Threat Model as "intrusion".

A Permissions-Policy header is specified as a list of (feature, allowed origins) pairs, thus:

Permissions-Policy: geolocation=(self "https://example.com"), camera=(), fullscreen=*

This example allows this page ("self") and <iframe>s from the origin example.com to use the navigator.geolocation APIs

from JavaScript; it allows this page and all subframes to use the full screen API, and it prohibits any page, this page included,

from using a camera to read video information. There is much more detail and a list of potential examples here.

The list of features that are handled by the Permissions-Policy header is large and may be in flux. Currently the list is maintained at https://github.com/w3c/webappsec-permissions-policy/blob/main/features.md.

Do

Browsers that support Permissions-Policy disallow powerful features in subframes by default, and you have to act to enable them!

This approach is private by default. If you find that subframes on your site require these permissions, you can selectively add them.

However, there is no permissions policy applied to the main page by default, and so scripts (including third-party scripts) that are

loaded by the main page are not restricted from attempting to use these features. For this reason, it is useful to apply a restrictive

Permissions-Policy to all pages by default, and then gradually add back in features that your pages require.

Examples of powerful features that Permissions-Policy affects include requesting the user's location, access to sensors (including

accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer), permission to go fullscreen, and requesting access to the user’s camera and microphone.

The (changing) full list of features is linked above.

Unfortunately, blocking all features by default and then selectively re-allowing them requires listing all features in the header,

which can feel rather inelegant. Nonetheless, such a Permissions-Policy header is a good place to start. permissionspolicy.com/

has a conveniently clickable generator to create such a header: using it to create a header which disables all features results in this:

Permissions-Policy: accelerometer=(), ambient-light-sensor=(), autoplay=(), battery=(), camera=(), cross-origin-isolated=(),

display-capture=(), document-domain=(), encrypted-media=(), execution-while-not-rendered=(), execution-while-out-of-viewport=(),

fullscreen=(), geolocation=(), gyroscope=(), keyboard-map=(), magnetometer=(), microphone=(), midi=(), navigation-override=(),

payment=(), picture-in-picture=(), publickey-credentials-get=(), screen-wake-lock=(), sync-xhr=(), usb=(), web-share=(), xr-spatial-tracking=()

Understand built-in privacy features in web browsers

In addition to the "build time" and "design time" protections, there are also privacy protections which happen at "run time": that is, privacy features implemented in browsers themselves to protect users. These are not features you can directly control or tap into as a site developer—they're product features—but they are features you should be aware of, because your sites may be affected by these product decisions in browsers. To give an example here of the way these browser protections may impact your site, if you have client-side JavaScript which waits for a third-party dependency to load before continuing with page setup, and that third-party dependency never loads at all, then your page setup may never complete and so the user is presented with a half-loaded page.

They include Intelligent Tracking Prevention in Safari (and the underlying WebKit engine), and Enhanced Tracking Protection in Firefox (and its engine, Gecko). These all make it difficult for third parties to build detailed profiles of your users.

Browser approaches on privacy features change frequently, and it’s important to stay up to date; the following list of protections

are correct at time of writing. Browsers may also implement other protections; these lists are not exhaustive. See the module on best practices

for ways to keep up with changes here, and be sure to test with upcoming browser versions for changes that may affect your projects.

Bear in mind that incognito/private browsing modes sometimes implement different settings from the browser’s default (third-party cookies may be blocked

by default in such modes, for example). Therefore, testing in incognito mode may not always be reflective of most users’ typical browsing experience if

they're not using private browsing. Also bear in mind that blocking cookies in various situations may mean that other storage solutions, such as window.localStorage,

are also blocked, not only cookies.

Chrome

- Third-party cookies are intended to be blocked in the future. As of this writing they are not blocked by default (but this can be enabled by a user): https://support.google.com/chrome/answer/95647 explains the details.

- Chrome's privacy features, and in particular the features in Chrome that communicate with Google and third-party services, are described at privacysandbox.com/.

Edge

- Third-party cookies are not blocked by default (but this can be enabled by a user).

- Edge's Tracking Prevention feature blocks trackers from unvisited sites and known harmful trackers are blocked by default.

Firefox

- Third-party cookies are not blocked by default (but this can be enabled by a user).

- Firefox's Enhanced Tracking Protection blocks by default tracking cookies, fingerprinting scripts, cryptominer scripts, and known trackers. (https://support.mozilla.org/kb/trackers-and-scripts-firefox-blocks-enhanced-track provides some more details).

- Third-party cookies are site-limited, so each site essentially has a separate cookie jar and can’t be correlated across sites (Mozilla calls this "Total Cookie Protection".

To get some insight into what may be blocked and to help debug issues, click the shield icon in the address bar or visit about:protections in Firefox (on desktop).

Safari

- Third-party cookies are blocked by default.

- As part of its Intelligent Tracking Prevention feature,

Safari reduces the referrer passed to other pages to be a top-level site rather than a specific page: (

https://something.example.com, rather thanhttps://something.example.com/this/specific/page). - Browser

localStoragedata is deleted after seven days.

(https://webkit.org/blog/10218/full-third-party-cookie-blocking-and-more/ summarizes these features.)

To get some insight into what may be blocked and to help debug issues, enable "Intelligent Tracking Prevention Debug Mode" in Safari's developer menu (on desktop). (See https://webkit.org/blog/9521/intelligent-tracking-prevention-2-3/ for more details.)

API proposals

Why do we need new APIs?

While new privacy-preserving features and policies in browser products help preserve user privacy, they also come with challenges. Many web technologies are usable for cross-site tracking despite being designed for and used for other purposes. For example, many identity federation systems we use every day rely on third-party cookies. Numerous advertising solutions that publishers rely on for revenue today are built on top of third-party cookies. Many fraud detection solutions rely on fingerprinting. What happens to these use cases when third-party cookies and fingerprinting go away?

It would be difficult and error-prone for browsers to differentiate use cases, and to reliably distinguish privacy-violating uses from others. This is why most major browsers have blocked third-party cookies and fingerprinting or intend to do so, to protect user privacy.

A new approach is needed: as third-party cookies are phased out and fingerprinting mitigated, developers need purpose-built APIs that meet the use cases (which haven’t gone away) but are designed in a privacy-preserving manner. The goal is to design and build APIs which can’t be used for cross-site tracking. Unlike the browser features described in the previous section, these technologies aspire to become cross-browser APIs.

Examples of API proposals

The following list isn’t comprehensive—it's a flavor of some of what’s being discussed.

Examples of API proposals to replace technologies built on third-party cookies:

- Identity use cases: FedCM

- Ads use cases: Private Click Measurement, Interoperable Private Attribution, Attribution Reporting, Topics, FLEDGE, PARAKEET.

Examples of API proposals to replace technologies built on passive tracking:

- Fraud detection use cases: Trust Tokens.

Examples of other proposals that other APIs can build on in a future without third-party cookies:

Additionally, another type of API proposal is emerging to try and have so-far browser-specific covert tracking mitigations. One example is Privacy Budget. Across these various use cases, the APIs that were initially proposed by Chrome live under the umbrella term of the Privacy Sandbox.

Global-Privacy-Control is a header that intends to communicate to a site that the user would like any collected personal data not to be shared with other sites. Its intention is similar to Do Not Track, which was discontinued.

Status of the API proposals

Most of these API proposals are not yet deployed, or are deployed only behind flags or in limited environments for experimentation.

This public incubation phase is important: browser vendors and developers collect discussion and experience with whether these APIs are useful and whether they actually do what they’re designed for. Developers, browser vendors, and other ecosystem actors use this phase to iterate on the API's design.

The best place to keep up to date with new APIs being proposed is currently the Privacy Group’s list of proposals on Github.

Do you need to use these APIs?

If your product is directly built on top of third-party cookies or techniques such as fingerprinting, you should get involved with these new APIs, experiment with them, and contribute your own experiences to the discussions and API design. In all other cases, you don’t necessarily need to know all the details on these new APIs at the time of writing, but it’s good to be aware of what’s coming.