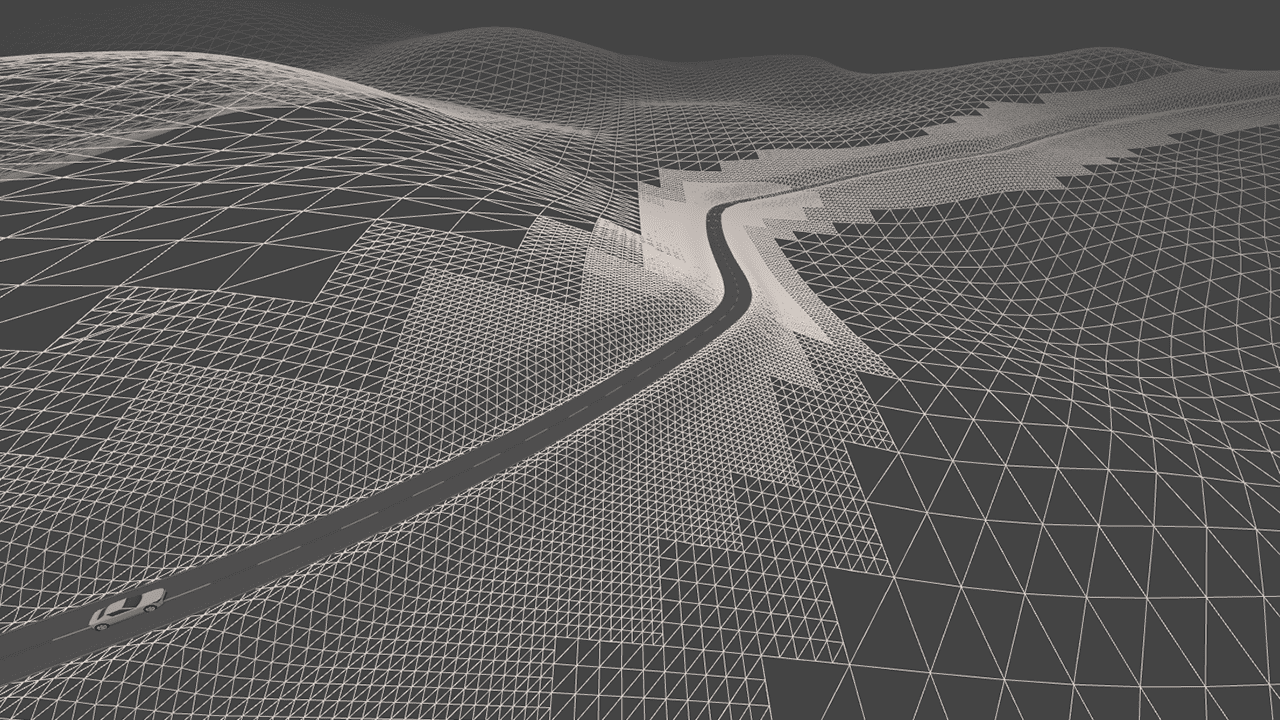

Discover the potential of WebGL with the infinite, procedurally-generated scenery of this casual driving game.

Slow Roads is a casual driving game with an emphasis on endlessly procedurally generated scenery, all hosted in the browser as a WebGL application. For many, such an intensive experience might seem out of place in the limited context of the browser—and indeed, redressing that attitude has been one of my goals with this project. In this article I'll be breaking down some of the techniques I used to navigate the performance hurdle in my mission to highlight the oft-overlooked potential of 3D in the web.

3D development in the browser

After releasing Slow Roads, I saw a recurring comment in the feedback: "I didn't know this was possible in the browser". If you share this sentiment, you're certainly not a minority; according to the 2022 State of JS survey, some 80% of developers have yet to experiment with WebGL. To me, it feels something of a shame that so much potential might be missed, especially when it comes to browser-based gaming. With Slow Roads I hope to bring WebGL further into the limelight, and perhaps reduce the number of developers who balk at the phrase "high-performance JavaScript game engine".

WebGL may seem mysterious and complex for many, but in recent years its development ecosystems have greatly matured into highly capable and convenient tools and libraries. It's now easier than ever for front-end developers to incorporate 3D UX into their work, even without prior experience in computer graphics. Three.js, the leading WebGL library, serves as the foundation for many expansions, including react-three-fiber which brings 3D components into the React framework. There are now also comprehensive web-based game editors such as Babylon.js or PlayCanvas which offer a familiar interface and integrated toolchains.

Despite the remarkable utility of these libraries, however, ambitious projects are eventually bound by technical limitations. Skeptics to the idea of browser-based gaming might highlight that JavaScript is single-threaded and resource-constrained. But navigating these limitations unlocks the hidden value: no other platform offers the same instant accessibility and mass compatibility enabled by the browser. Users on any browser-capable system can begin playing in one click, with no need to install applications and no need to sign in to services. Not to mention that developers enjoy the elegant convenience of having robust front-end frameworks available for building UI, or handling networking for multiplayer modes. These values, in my opinion, are what make the browser such an excellent platform for both players and developers alike—and, as demonstrated by Slow Roads, the technical limitations might often be reducible to a design problem.

Achieving smooth performance in Slow Roads

Since the core elements of Slow Roads involve high-speed motion and expensive scenery generation, the need for smooth performance underlined my every design decision. My main strategy was to start with a pared-down gameplay design that allowed for contextual short-cuts to be taken within the engine's architecture. On the downside this means trading off some nice-to-have features in the pursuit of minimalism, but results in a bespoke, hyper-optimized system that plays nicely across different browsers and devices.

Here follows a breakdown of the key components that keep Slow Roads lean.

Shaping the environment engine around the gameplay

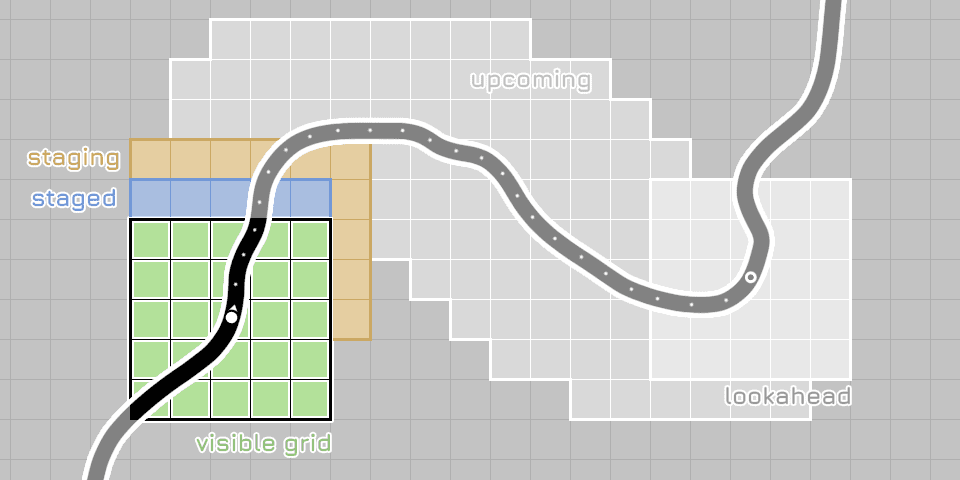

As the key component of the game, the environment generation engine is unavoidably expensive, justifiably taking the greatest proportion of the budgets for memory and compute. The trick used here is in scheduling and distributing the heavy computation over a period of time, so as not to interrupt the framerate with performance spikes.

The environment is composed of tiles of geometry, differing in size and resolution (categorized as "levels of detail" or LoDs) depending on how close they will appear to the camera. In typical games with a free-roaming camera, different LoDs must be constantly loaded and unloaded to detail the player's surroundings wherever they may choose to go. This can be an expensive and wasteful operation, especially when the environment itself is dynamically generated. Fortunately, this convention can be entirely subverted in Slow Roads thanks to the contextual expectation that the user should stay on the road. Instead, high-detail geometry can be reserved for the narrow corridor directly flanking the route.

The midline of the road itself is generated far ahead of the player's arrival, allowing for accurate prediction of exactly when and where the environment detail will be needed. The result is a lean system that can proactively schedule expensive work, generating just the minimum needed at each point in time, and with no wasted effort on details that won't be seen. This technique is only possible because the road is a single, non-branching path—a good example of making gameplay trade-offs that accommodate architectural short-cuts.

Being picky with the laws of physics

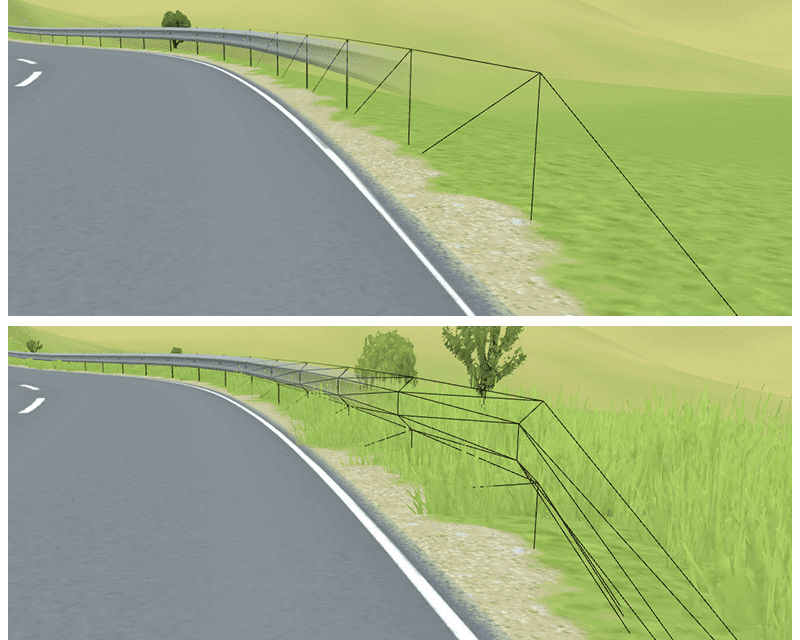

Second to the computational demand of the environment engine is the physics simulation. Slow Roads uses a custom, minimal physics engine which takes every short-cut available.

The major saving here is to avoid simulating too many objects in the first place—leaning into the minimal, zen context by discounting things like dynamic collisions and destructible objects. The assumption that the vehicle will stay on the road means that collisions with off-road objects can reasonably be ignored. Additionally, the encoding of the road as a sparse midline enables elegant tricks for fast collision detection with the road surface and guard rails, all based on a distance check to the road's center. Off-road driving then becomes more expensive, but this is another example of a fair trade-off suited to the context of the gameplay.

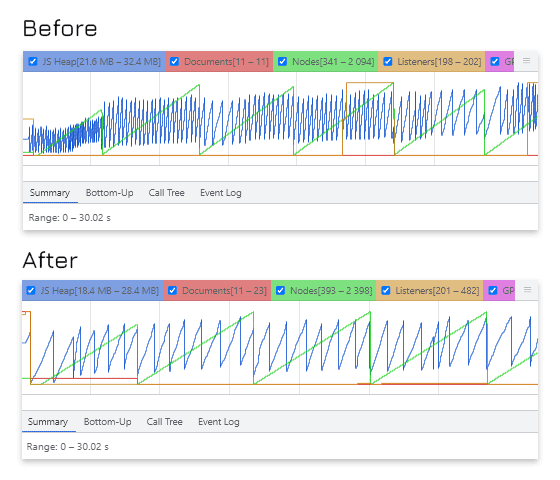

Managing the memory footprint

As another browser-restrained resource, it's important to manage memory with care—despite the fact JavaScript is garbage-collected. It can be easy to overlook, but declaring even small amounts of new memory within a game loop can snowball into significant issues when running at 60Hz. Besides eating up the user's resources in a context where they're likely multitasking, large garbage collections can take several frames to complete, causing noticeable stutters. To avoid this, loop memory can be pre-allocated in class variables at initialisation and recycled in each frame.

It's also highly important that heavier data structures, such as geometries and their associated data buffers, are managed economically. In an infinitely-generated game like Slow Roads, most of the geometry exists on a sort of treadmill - once an old piece falls behind into the distance, its data structures can be stored and recycled again for an upcoming piece of the world, a design pattern known as object pooling.

These practices help to prioritize lean execution, with the sacrifice of some code simplicity. In high-performance contexts it's

important to be mindful of how convenience features sometimes borrow from the client for the benefit of the developer. For example, methods

like Object.keys() or Array.map() are incredibly handy, but it's easy to overlook that each creates a new array for their return

value. Understanding the inner workings of such black-boxes can help to tighten up your code and avoid sneaky performance hits.

Reducing load time with procedurally-generated assets

While runtime performance should be the primary concern for game developers, the usual axioms concerning initial web page load time still hold true. Users may be more forgiving when knowingly accessing heavy content, but long load times can still be detrimental to the experience, if not user retention. Games often require large assets in the form of textures, sounds, and 3D models, and at a minimum these should be carefully compressed wherever detail can be spared.

Alternatively, procedurally generating assets on the client can avoid lengthy transfers in the first place. This is a huge benefit for users on slow connections, and gives the developer more direct control over how their game is constituted—not just for the initial loading step, but also when it comes to adapting levels of details for different quality settings.

Most of the geometry in Slow Roads is procedurally generated and simplistic, with custom shaders combining multiple textures to bring the detail. The drawback is that these textures can be heavy assets, though there are further opportunities for savings here, with methods such as stochastic texturing able to achieve greater detail from small source textures. And at an extreme level, it's also possible to generate textures entirely on the client with tools such as texgen.js. The same is even true for audio, with the Web Audio API allowing for sound generation with audio nodes.

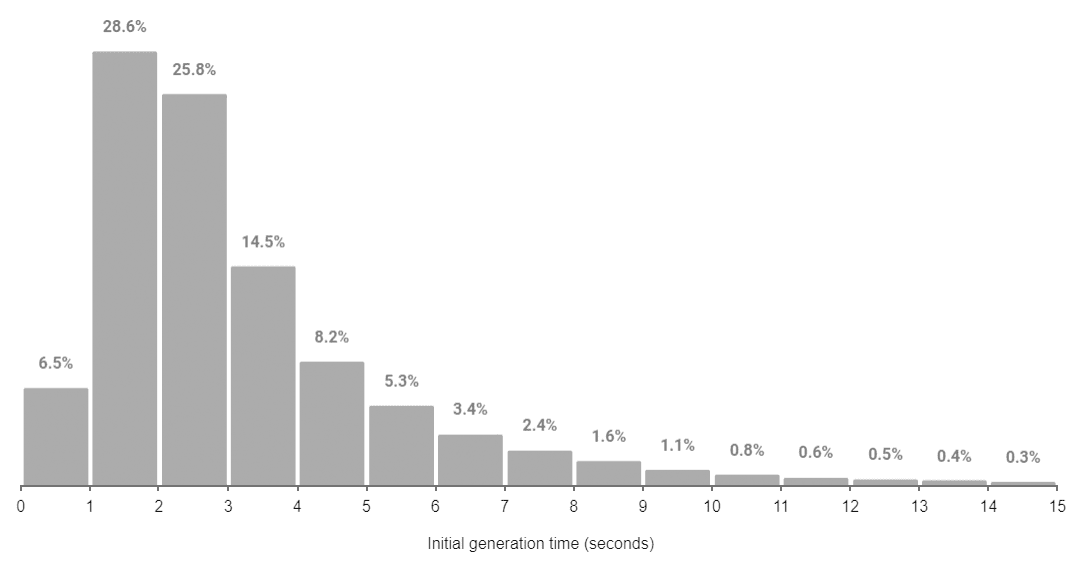

With the benefit of procedural assets, generating the initial environment takes just 3.2 seconds on average. To best take advantage of the small up-front download size, a simple splash screen greets new visitors and postpones the expensive scene initialisation until after an affirmative button press. This also acts as a convenient buffer for bounced sessions, minimizing wasted transfer of dynamically-loaded assets.

Taking an agile approach to late optimization

I've always considered the codebase for Slow Roads to be experimental, and as such have taken a fiercely agile approach to development. When working with a complex and rapidly-evolving system architecture, it can be difficult to predict where the important bottlenecks may occur. The focus should be on implementing the desired features quickly, rather than cleanly, and then working backwards to optimize systems where it really counts. The performance profiler in Chrome DevTools is invaluable for this step, and has helped me to diagnose some major issues with earlier versions of the game. Your time as a developer is valuable, so be sure you aren't spending time deliberating over problems that may prove insignificant or redundant.

Monitoring the user experience

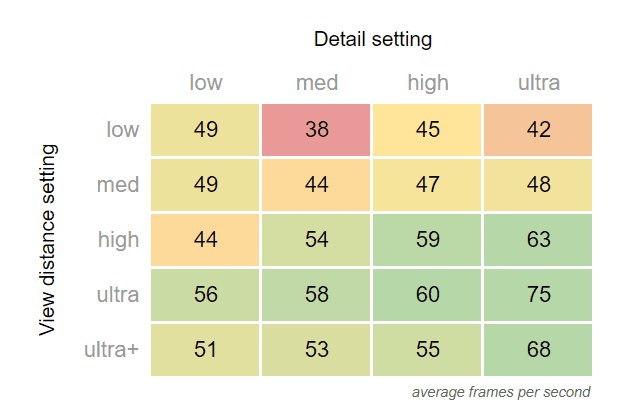

While implementing all of these tricks, it's important to be sure the game performs as expected in the wild. Accommodating a range of hardware capabilities is a staple aspect of any game development, but web games can target a much broader spectrum comprising both top-end desktops and decade-old mobile devices at once. The simplest way to approach this is by offering settings for adapting the most likely bottlenecks in your codebase—for both GPU- and CPU-intensive tasks—as revealed by your profiler.

Profiling on your own machine can only cover so much, however, so it's valuable to close the feedback loop with your users in some way. For Slow Roads I run simple analytics which report on performance along with contextual factors such as screen resolution. These analytics are sent to a basic Node backend using socket.io, along with any written feedback the user submits via the in-game form. In the early days, these analytics caught a lot of important issues that could be mitigated with simple changes to the UX, such as highlighting the settings menu when a consistently low FPS is detected, or warning that a user may need to enable hardware acceleration if the performance is particularly poor.

The slow roads ahead

Even after taking all of these measures, there remains a significant portion of the player base that needs to play on lower settings—primarily those using lightweight devices which lack a GPU. While the range of quality settings available leads to a fairly even performance distribution, only 52% of players achieve above 55 FPS.

Fortunately, there are still many opportunities for making performance savings. Alongside adding further rendering tricks to reduce GPU demand, I hope to experiment with web workers in parallelising the environment generation in the near term, and may eventually see a need for incorporating WASM or WebGPU into the codebase. Any headroom I'm able to free up will allow for richer and more diverse environments, which will be the enduring goal for the remainder of the project.

As hobby projects go, Slow Roads has been an overwhelmingly fulfilling way to demonstrate how surprisingly elaborate, performant, and popular browser games can be. If I've been successful in piquing your interest in WebGL, know that technologically Slow Roads is a fairly shallow example of its full capabilities. I strongly encourage readers to explore the Three.js showcase, and those interested in web game development in particular would be welcome to the community at webgamedev.com.