Accessible images may seem like a quick topic at first glance—you add some "alt text" to an image, and you are done. But, the topic is more nuanced than some people think. In this section, we'll review:

- How to update the code to make images accessible.

- What information should be shared with users and where to share it.

- Additional ways to improve your images to support people with disabilities.

Image purpose and context

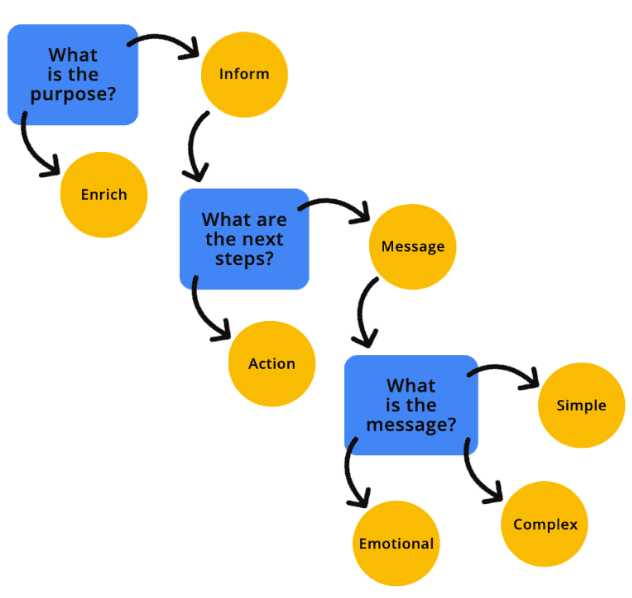

Before you write even one line of code, think about the point image's purpose, where it will live, and how it will be used. Asking yourself these questions can help you determine how best to convey the information to a person using assistive technology (AT), such as a screen reader.

You may ask yourself:

- Is the image essential to understanding the context of the feature or page?

- What type of information is the image trying to convey?

- Is the image simple or complex?

- Does the image elicit emotion or prompt the user to act?

- Or is the image just visual "eye candy" with no real purpose?

A visual flowchart, such as an image decision tree, can help you decide which category your image belongs to.

Try hiding the images on your site or web app using a browser extension or other methods. Then ask yourself: "Do I understand the content that remains?" If the answer is yes, it is most likely a decorative image. If not, the image is instead informative in some way and contextually necessary. Once you determine the image's purpose, you can determine the most accurate way to code for it.

Decorative images

A decorative image is a visual element that doesn't add additional context or information that allows the user to better understand the context. Decorative images are supplemental and may provide style rather than substance.

If you decide an image is decorative, the image must be programmatically hidden from ATs. When you program an image to be hidden, it signals to the AT that the image is not needed to understand the page's content, context, or action. There are many ways to hide images, including using an empty or null text alternative, applying ARIA, or adding the image as a CSS background. Here are a few examples of how to hide a decorative image from users.

Empty or null alt

An empty or null alternative text attribute differs from a missing alternative text attribute. If the alternative text attribute is missing, the AT might read out the filename or surrounding content to give the user more information about the image.

Role set to presentation or none

A role set to

presentation or none

removes an element's semantics from exposure to the accessibility tree.

Meanwhile, aria-hidden= "true"

removes the entire element—and all of its children—from the

accessibility API.

<!-- All of these choices lead to the same result. -->

<img src=".../Ladybug.jpg" role="presentation">

<img src=".../Ladybug.jpg" role="none">

<img src=".../Ladybug.jpg" aria-hidden="true">

Use aria-hidden with caution as it may hide elements that

you don't want to hide.

Images in CSS

When you add a background image with CSS, a screen reader cannot detect the image file. Be sure you want the image to be hidden before applying this method.

Informative images

An informative image is an image that conveys a concept, idea, or emotion. Informative images include photos of real-world objects, essential icons, simple drawings, and images of text.

If your image is informative, you should include programmatic alternative text describing the purpose of the image. Alternative image descriptions—often abbreviated as "alt text"—give AT users more context about an image and help them better understand an image's message or intent.

Alternative descriptions for the

<img> elements

are added by including the alt attribute, regardless of the file type it

points to, such as .jpg, .png, .svg, and others.

<img src=".../Ladybug_Swarm.jpg" alt="A swarm of red ladybugs is resting on the leaves of my prize rose bush.">

When you use <svg> elements inline, however, you need to pay attention to accessibility.

First, since SVGs are semantically coded, AT will skip over them by default.

If you have a decorative image, this is not an issue—the AT will ignore

it as intended. But if you have an informative image, an ARIA role="img"

needs to be added to the pattern for the AT to recognize it as an image.

Second, <svg> elements do not use the alt attribute, so

different coding methods must be

used instead to add alternative descriptions to your informative images.

<svg role="img" ...>

<title>Cartoon drawing of a red, black, and gray ladybug.</title>

</svg>

Functional images

A functional image is connected to an action. An example of a functional image is a logo that links to the home page, a magnifying glass used as a search button, or a social media icon that directs you to a different website or app.

Like informative images, functional images must include an alternative description to inform all users of their purpose. Unlike an informative image, each functional image needs to describe the image's action—not the visual aspects.

In the logo example, the image is both informative and actionable as it is both an image that conveys information and behaves as a link. In cases like these, you can add alternative descriptions to each element—but it is not a requirement.

One way to add alternative descriptions to images is through visually hidden text. When you use this method, the text will be read by screen readers because it is in the DOM, but it is visually hidden with the help of custom CSS.

You can see from the code snippet that "Navigate to the homepage" is the wrapper title, and the image alternative text is "Lovely Ladybugs for your Lawn." When you listen to the logo code with a screen reader, you hear both the visual and the action conveyed in one image.

<div title="Navigate to the homepage">

<a href="/">

<img src=".../Ladybug_Logo.png" alt="Lovely Ladybugs for your Lawn"/>

</a>

</div>

Complex images

A complex image often requires more explanation than a decorative, informational, or functional image. It requires both a short and a long alternative description to convey the full message. Complex images include infographics, maps, graphs/charts, and complex illustrations.

As with the other image types, there are different methods you can use to add alternative descriptions to your complex images.

<img src=".../Ladybug_Anatomy.svg" alt="Diagram of the anatomy of a ladybug.">

<a href="ladybug-science.html">Learn more about the anatomy of a ladybug</a>

One way to add additional explanation to an image is to link out to a resource or provide a jump link to a longer explanation later on the page. This method is a good choice, not only for AT users but also helps people with disabilities—such as cognitive, learning, and reading disabilities—who might benefit from having this additional image information readily available on the screen instead of buried in the code.

Another method you can use is to append the aria-describedby attribute to the

<img> element. You can programmatically link the image to an ID containing a

longer description. This method creates a strong association between the image

and the full description. The extended description can be displayed on the

screen or visually hidden—but consider keeping it visible to support even

more people.

One other way to group short alternative descriptions with a longer one is to

use the<figure> and <figcaption> elements. These elements act similarly to

aria-describedby in that it semantically groups elements, forming a stronger

association between the image and its description.

Adding ARIA role="group" ensures backward compatibility with older web

browsers that don't support the semantics of the <figure> element.

Alternative text best practices

Of course, including alternate text is not enough. The text should also be meaningful. For example, if your image is about a swarm of ladybugs chewing the leaves of your prize rose bush, but your alternative text reads "bugs," would that convey the full message and intent of the image? Definitely not.

Alternative descriptions need to capture as much relevant visual information as possible and be succinct. While there is no limit to the number of characters a screen reader can read, it is usually advised to cap your alternative text to 150 characters or less to avoid reader fatigue. If you need to add additional context to the image, you can use one of the complex image patterns, add caption text, or further describe the image in the main copy.

Some additional alternative text best practices include:

- Avoid using words like "image of" or "photo of" in the description, as the screen reader will identify these file types for you.

- When naming your images, be as consistent and accurate as possible. Image names are a fallback when the alternative text is missing or ignored.

- Avoid using non-alpha characters (for example, #, 9, &) and use dashes between words rather than underscores in your image names or alternative text.

- Use proper punctuation whenever possible. Without it, the image descriptions will sound like one long, never-ending, run-on sentence.

- Write alternative text like a human and not a robot. Keyword stuffing does not benefit anyone—people using screen readers will be annoyed, and search engine algorithms will penalize you.

Check your understanding

Test your knowledge.

How can you make complex images accessible?

aria-describedby attribute to the image.