Improve performance by using a content delivery network.

Content delivery networks (CDNs) improve site performance by using a distributed network of servers to deliver resources to users. Because CDNs reduce server load, they reduce server costs and are well-suited to handling traffic spikes. This article discusses how CDNs work and provides platform-agnostic guidance on choosing, configuring, and optimizing a CDN setup.

Overview

A content delivery network consists of a network of servers that are optimized for quickly delivering content to users. Although CDNs are arguably best known for serving cached content, CDNs can also improve the delivery of uncacheable content. Generally speaking, the more of your site delivered by your CDN, the better.

At a high-level, the performance benefits of CDNs stem from a handful of principles: CDN servers are located closer to users than origin servers and therefore have a shorter round-trip time (RTT) latency; networking optimizations allow CDNs to deliver content more quickly than if the content was loaded "directly" from the origin server; lastly, CDN caches eliminate the need for a request to travel to the origin server.

Resource delivery

Although it may seem non-intuitive, using a CDN to deliver resources (even uncacheable ones) will typically be faster than having the user load the resource "directly" from your servers.

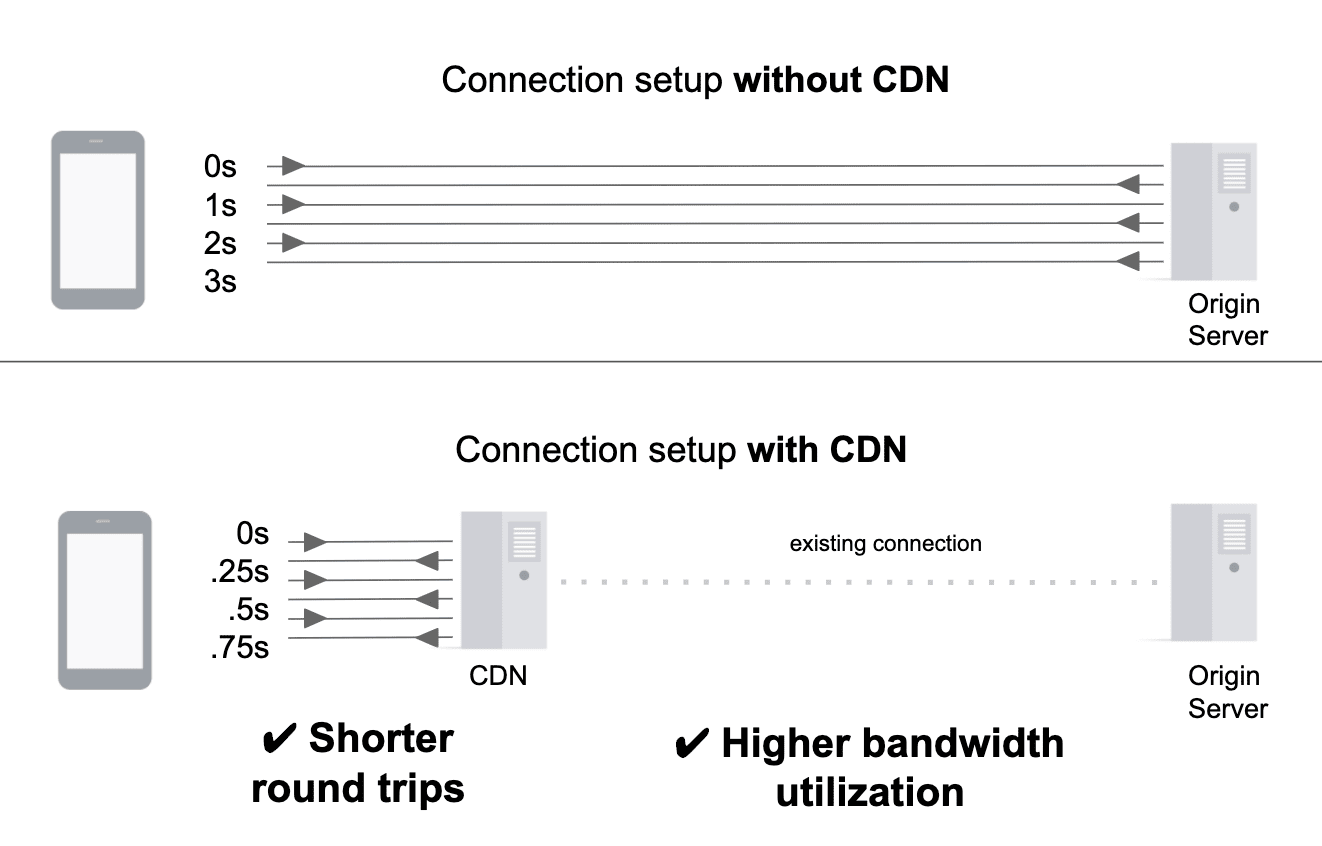

When a CDN is used to deliver resources from the origin, a new connection is established between the client and a nearby CDN server. The remainder of the journey (in other words, the data transfer between the CDN server and origin) occurs over the CDN's network - which often includes existing, persistent connections with the origin. The benefits of this are twofold: terminating the new connection as close to the user as possible eliminates unnecessary connection setup costs (establishing a new connection is expensive and requires multiple roundtrips); using a pre-warmed connection allows data to be immediately transferred at the maximum possible throughput.

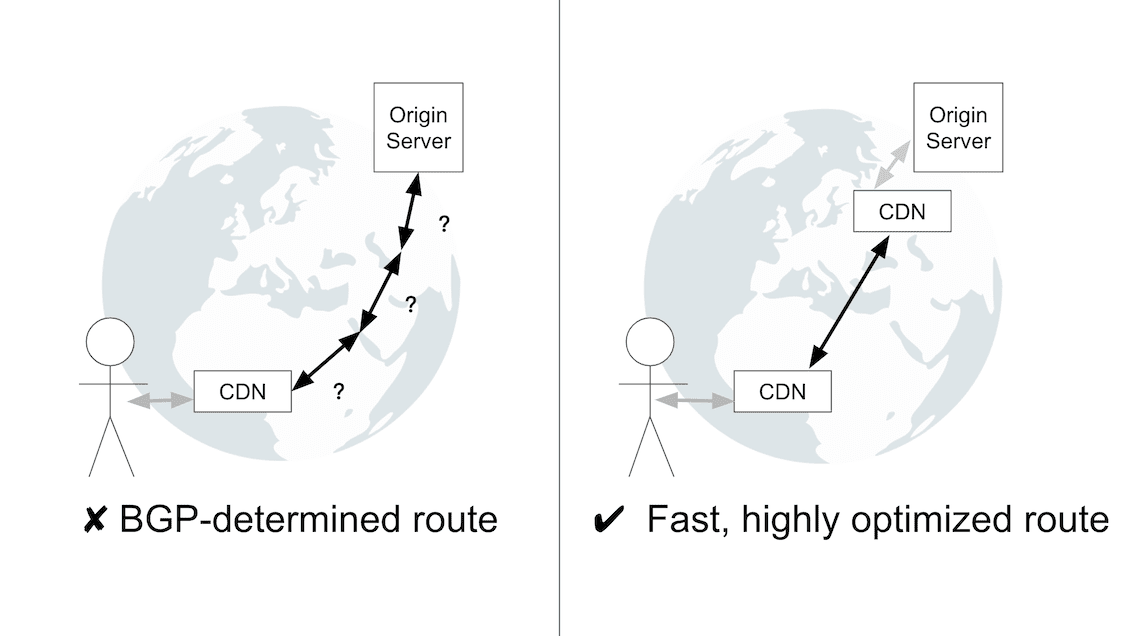

Some CDNs improve upon this even further by routing traffic to the origin through multiple CDN servers spread across the Internet. Connections between CDN servers occur over reliable and highly optimized routes, rather than routes determined by the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). Although BGP is the internet's de facto routing protocol, its routing decisions are not always performance-oriented. Therefore, BGP-determined routes are likely to be less performant than the finely-tuned routes between CDN servers.

Caching

Caching resources on a CDN's servers eliminates the need for a request to travel all the way to the origin in order to be served. As a result, the resource is delivered more quickly; this also reduces the load on the origin server.

Adding resources to the cache

The most commonly used method of populating CDN caches is to have the CDN "pull" resources as they are needed - this is known as "origin pull". The first time that a particular resource is requested from the cache the CDN will request it from the origin server and cache the response. In this manner, the contents of the cache are built-up over time as additional uncached resources are requested.

Removing resources from the cache

CDNs use cache eviction to periodically remove not-so-useful resources from the cache. In addition, site owners can use purging to explicitly remove resources.

Cache eviction

Caches have a finite storage capacity. When a cache nears its capacity, it makes room for new resources by removing resources that haven't been accessed recently, or which take up a lot of space. This process is known as cache eviction. A resource being evicted from one cache does not necessarily mean that it has been evicted from all caches in a CDN network.

Purging

Purging (also known as "cache invalidation") is a mechanism for removing a resource from a CDN's caches without having to wait for it to expire or be evicted. It is typically executed via an API. Purging is critical in situations where content needs to be retracted (for example, correcting typos, pricing errors, or incorrect news articles). On top of that, it can also play a crucial role in a site's caching strategy.

If a CDN supports near instant purging, purging can be used as a mechanism for managing the caching of dynamic content: cache dynamic content using a long TTL, then purge the resource whenever it is updated. In this way, it is possible to maximize the caching duration of a dynamic resource, despite not knowing in advance when the resource will change. This technique is sometimes referred to as "hold-till-told caching".

When purging is used at scale it is typically used in conjunction with a concept known as "cache tags" or "surrogate cache keys". This mechanism allows site owners to associate one or more additional identifiers (sometimes referred to as "tags") with a cached resource. These tags can then be used to carry out highly granular purging. For example, you might add a "footer" tag to all resources (for example,

/about,/blog) that contain your site footer. When the footer is updated, instruct your CDN to purge all resources associated with the "footer" tag.

Cacheable resources

If and how a resource should be cached depends on whether it is public or private; static or dynamic.

Private and public resources

Private Resources

Private resources contain data intended for a single user and therefore should not be cached by a CDN. Private resources are indicated by the

Cache-Control: privateheader.Public Resources

Public resources do not contain user-specific information and therefore are cacheable by a CDN. A resource may be considered cacheable by a CDN if it does not have a

Cache-Control: no-storeorCache-Control: privateheader. The length of time that a public resource can be cached depends on how frequently the asset changes.

Dynamic and static content

Dynamic content

Dynamic content is content that changes frequently. An API response and a store homepage are examples of this content type. However, the fact that this content changes frequently doesn't necessarily preclude it from being cached. During periods of heavy traffic, caching these responses for very short periods of time (for example, 5 seconds) can significantly reduce the load on the origin server, while having minimal impact on data freshness.

Static content

Static content changes infrequently, if ever. Images, videos, and versioned libraries are typically examples of this content type. Because static content does not change, it should be cached with a long Time to Live (TTL) - for example, 6 months or 1 year.

Choosing a CDN

Performance is typically a top consideration when choosing a CDN. However, the other features that a CDN offers (for example, security and analytics features), as well as a CDN's pricing, support, and onboarding are all important to consider when choosing a CDN.

Performance

At a high-level, a CDN's performance strategy can be thought of in terms of the tradeoff between minimizing latency and maximizing cache hit ratio. CDNs with many points of presence (PoPs) can deliver lower latency but may experience lower cache hit ratios as a result of traffic being split across more caches. Conversely, CDNs with fewer PoPs may be located geographically further from users, but can achieve higher cache hit ratios.

As a result of this tradeoff, some CDNs use a tiered approach to caching: PoPs located close to users (also known as "edge caches") are supplemented with central PoPs that have higher cache hit ratios. When an edge cache can't find a resource, it will look to a central PoP for the resource. This approach trades slightly greater latency for a higher likelihood that the resource can be served from a CDN cache - though not necessarily an edge cache.

The tradeoff between minimizing latency and maximizing cache hit ratio is a spectrum. No particular approach is universally better; however, depending on the nature of your site and its user base, you may find that one of these approaches delivers significantly better performance than the other.

It's also worth noting that CDN performance can vary significantly depending on geography, time of day, and even current events. Although it's always a good idea to do your own research on a CDN's performance, it can be difficult to predict the exact performance you'll get from a CDN.

Effects on Largest Contentful Paint (LCP)

As outlined before in this article, the primary purpose of a CDN is to reduce latency by distributing resources to servers that are geographically closer to users. Because of this, a CDN's primary benefit is that it improves loading performance. In particular, a resource's Time to First Byte (TTFB) can be significantly improved when introducing a CDN into your website's server-side architecture.

While TTFB is not a user-centric performance metric, it is an important metric for diagnosing issues with Largest Contentful Paint (LCP), which is a user-centric metric.

CDNs are particularly effective at improving LCP as they can improve both the document delivery (by reducing TTFB in connection setup and in caching the document) and in improving delivery of any static resources needed to render the LCP element.

Additional features

CDNs typically offer a wide variety of features in addition to their core CDN offering. Commonly offered features include: load balancing, image optimization, video streaming, edge computing, and security products.

How to setup and configure a CDN

Ideally you should use a CDN to serve your entire site. At a high-level, the setup process for this consists of signing up with a CDN provider, then updating your CNAME DNS record to point at the CDN provider. For example, the CNAME record for www.example.com might point to example.my-cdn.com. As a result of this DNS change, traffic to your site will be routed through the CDN.

If using a CDN to serve all resources is not an option, you can configure a CDN to only serve a subset of resources - for example, only static resources. You can do this by creating a separate CNAME record that will only be used for resources that should be served by the CDN. For example, you might create a static.example.com CNAME record that points to example.my-cdn.com. You would also need to rewrite the URLs of resources being served by the CDN to point to the static.example.com subdomain that you created.

Although your CDN will be set up at this point, there will likely be inefficiencies in your configuration. The next two sections of this article will explain how to get the most out of your CDN by increasing cache hit ratio and enabling performance features.

Improving cache hit ratio

An effective CDN setup will serve as many resources as possible from the cache. This is commonly measured by cache hit ratio (CHR). Cache hit ratio is defined as the number of cache hits divided by the number of total requests during a given time interval.

A freshly initialized cache will have a CHR of 0 but this increases as the cache is populated with resources. A CHR of 90% is a good goal for most sites. Your CDN provider should supply you with analytics and reporting regarding your CHR.

When optimizing CHR, the first thing to verify is that all cacheable resources are being cached and cached for the correct length of time. This is a simple assessment that should be undertaken by all sites.

The next level of CHR optimization, broadly speaking, is to fine tune your CDN settings to make sure that logically equivalent server responses aren't being cached separately. This is a common inefficiency that occurs due to the impact of factors like query params, cookies, and request headers on caching.

Initial audit

Most CDNs will provide cache analytics. In addition, tools like WebPageTest and Lighthouse can also be used to quickly verify that all of a page's static resources are being cached for the correct length of time. This is accomplished by checking the HTTP Cache headers of each resource. Caching a resource using the maximum appropriate Time To Live (TTL) will avoid unnecessary origin fetches in the future and therefore increase CHR.

At a minimum, one of these headers typically needs to be set in order for a resource to be cached by a CDN:

Cache-Control: max-age=Cache-Control: s-maxage=Expires

In addition, although it does not impact if or how a resource is cached by a CDN, it is good practice to also set the Cache-Control: immutable directive.Cache-Control: immutable indicates that a resource "will not be updated during its freshness lifetime". As a result, the browser will not revalidate the resource when serving it from the browser cache, thereby eliminating an unnecessary server request. Unfortunately, this directive is only supported by Firefox and Safari - it is not supported by Chromium-based browsers. This issue tracks Chromium support for Cache-Control: immutable. Starring this issue can help encourage support for this feature.

For a more detailed explanation of HTTP caching, refer to Prevent unnecessary network requests with the HTTP Cache.

Fine tuning

A slightly simplified explanation of how CDN caches work is that the URL of a resource is used as the key for caching and retrieving the resource from the cache. In practice, this is still overwhelmingly true, but is complicated slightly by the impact of things like request headers and query params. As a result, rewriting request URLs is an important technique for both maximizing CHR and ensuring that the correct content is served to users. A properly configured CDN instance strikes the correct balance between overly granular caching (which hurts CHR) and insufficiently granular caching (which results in incorrect responses being served to users).

Query params

By default, CDNs take query params into consideration when caching a resource. However, small adjustments to query param handling can have a significant impact on CHR. For example:

Unnecessary query params

By default, a CDN would cache

example.com/blogandexample.com/blog?referral_id=2zjkseparately even though they are likely the same underlying resource. This is fixed by adjusting a CDN's configuration to ignore thereferral\_idquery param.Query param order

A CDN will cache

example.com/blog?id=123&query=dogsseparately fromexample.com/blog?query=dogs&id=123. For most sites, query param order does not matter, so configuring the CDN to sort the query params (thereby normalizing the URL used to cache the server response) will increase CHR.

Vary

The Vary response header informs caches that the server response corresponding to a particular URL can vary depending on the headers set on the request (for example, the Accept-Language or Accept-Encoding request headers). As a result, it instructs a CDN to cache these responses separately. The Vary header is not widely supported by CDNs and may result in an otherwise cacheable resource not being served from a cache.

Although the Vary header can be a useful tool, inappropriate usage hurts CHR. In addition, if you do use Vary, normalizing request headers will help improve CHR. For example, without normalization the request headers Accept-Language: en-US and Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9 would result in two separate cache entries, even though their contents would likely be identical.

Cookies

Cookies are set on requests via the Cookie header; they are set on responses via the Set-Cookie header. Unnecessary use of Set-Cookie header should be avoided given that caches will typically not cache server responses containing this header.

Performance features

This section discusses performance features that are commonly offered by CDNs as part of their core product offering. Many sites forget to enable these features, thereby losing out on easy performance wins.

Compression

All text-based responses should be compressed with either gzip or Brotli. If you have the choice, choose Brotli over gzip. Brotli is a newer compression algorithm, and compared to gzip, it can achieve higher compression ratios.

There are two types of CDN support for Brotli compression: "Brotli from origin" and "automatic Brotli compression".

Brotli from origin

Brotli from origin is when a CDN serves resources that were Brotli-compressed by the origin. Although this may seem like a feature that all CDNs should be able to support out of the box, it requires that a CDN be able to cache multiple versions (in other words, gzip-compressed and Brotli-compressed versions) of the resource corresponding to a given URL.

Automatic Brotli compression

Automatic Brotli compression is when resources are Brotli compressed by the CDN. CDNs can compress both cacheable and non-cacheable resources.

The first time that a resource is requested it is served using "good enough" compression - for example, Brotli-5. This type of compression is applicable to both cacheable and non-cacheable resources.

Meanwhile, if a resource is cacheable, the CDN will use offline processing to compress the resource at a more powerful but far slower compression level - for example, Brotli-11. Once this compression completes, the more compressed version will be cached and used for subsequent requests.

Compression best practices

Sites that want to maximize performance should apply Brotli compression at both their origin server and CDN. Brotli compression at the origin minimizes the transfer size of resources that can't be served from the cache. To prevent delays in serving requests, the origin should compress dynamic resources using a fairly conservative compression level - for example, Brotli-4; static resources can be compressed using Brotli-11. If an origin does not support Brotli, gzip-6 can be used to compress dynamic resources; gzip-9 can be used to compress static resources.

TLS 1.3

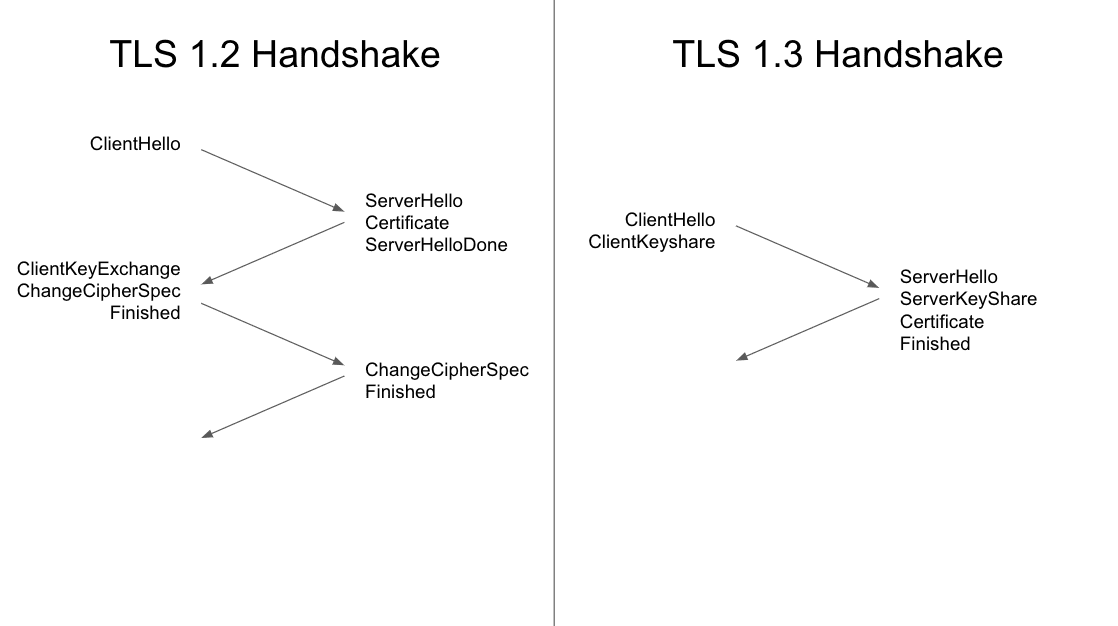

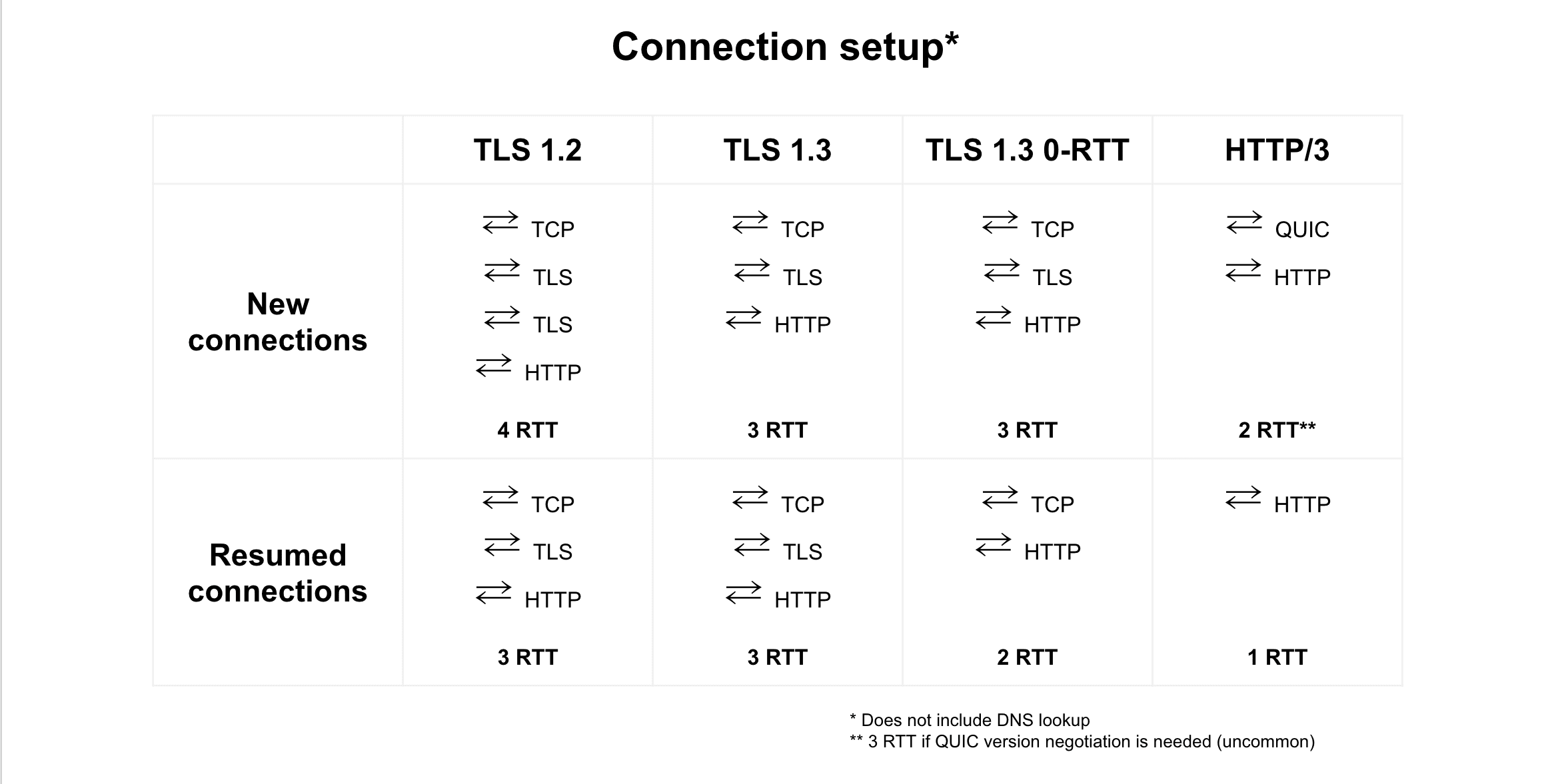

TLS 1.3 is the newest version of Transport Layer Security (TLS), the cryptographic protocol used by HTTPS. TLS 1.3 provides better privacy and performance compared to TLS 1.2.

TLS 1.3 shortens the TLS handshake from two roundtrips to one. For connections using HTTP/1 or HTTP/2, shortening the TLS handshake to one roundtrip effectively reduces connection setup time by 33%.

HTTP/2 and HTTP/3

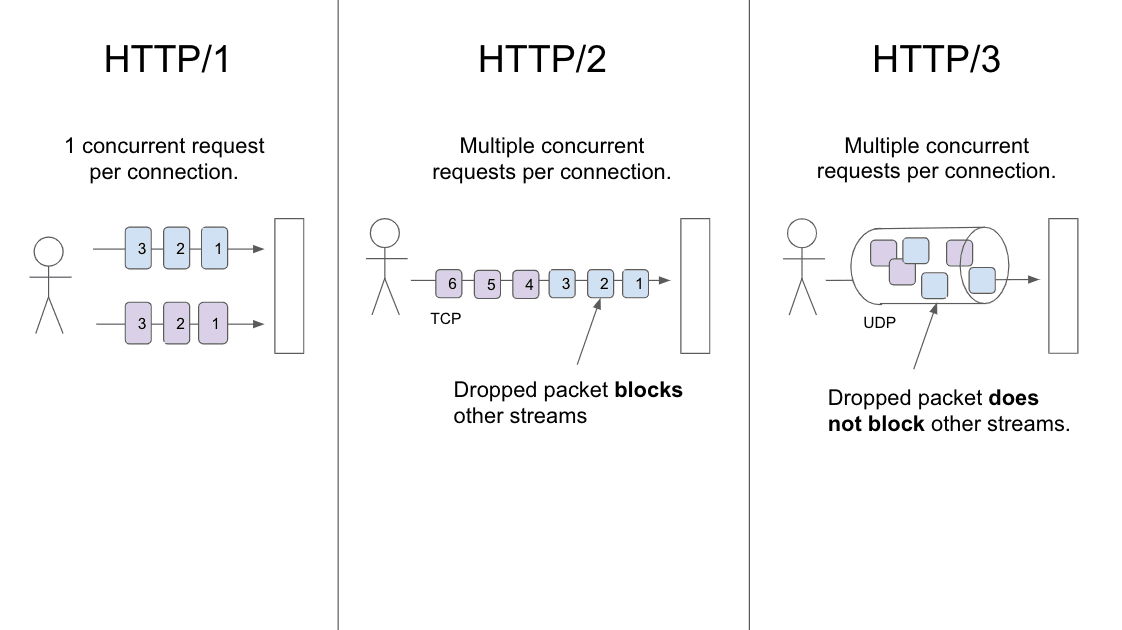

HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 both provide performance benefits over HTTP/1. Of the two, HTTP/3 offers greater potential performance benefits. HTTP/3 isn't fully standardized yet, but it will be widely supported once this occurs.

HTTP/2

If your CDN hasn't already enabled HTTP/2 by default, you should consider turning it on. HTTP/2 provides multiple performance benefits over HTTP/1 and is supported by all major browsers. Performance features of HTTP/2 include: multiplexing, stream prioritization, and header compression.

Multiplexing

Multiplexing is arguably the most important feature of HTTP/2. Multiplexing enables a single TCP connection to serve multiple request-response pairs at the same time. This eliminates the overhead of unnecessary connection setups; given that the number of connections that a browser can have open at a given time is limited, this also has the implication that the browser is now able to request more of a page's resources in parallel. Multiplexing theoretically removes the need for HTTP/1 optimizations like concatenation and sprite sheets - however, in practice, these techniques will remain relevant given that larger files compress better.

Stream prioritization

Multiplexing enables multiple concurrent streams; stream prioritization provides an interface for communicating relative priority of each of these streams. This helps the server to send the most important resources first - even if they weren't requested first.

Stream prioritization is expressed by the browser via a dependency tree and is merely a statement of preference: in other words, the server is not obligated to meet (or even consider) the priorities supplied by the browser. Stream prioritization becomes more effective when more of a site is served through a CDN.

CDN implementations of HTTP/2 resource prioritization vary wildly. To identify whether your CDN fully and properly supports HTTP/2 resource prioritization, check out Is HTTP/2 Fast Yet?.

Although switching your CDN instance to HTTP/2 is largely a matter of flipping a switch, it's important to thoroughly test this change before enabling it in production. HTTP/1 and HTTP/2 use the same conventions for request and response headers - but HTTP/2 is far less forgiving when these conventions aren't adhered to. As a result, non-spec practices like including non-ASCII or uppercase characters in headers may begin causing errors once HTTP/2 is enabled. If this occurs, a browser's attempts to download the resource will fail. The failed download attempt will be visible in the "Network" tab of DevTools. In addition, the error message "ERR_HTTP2_PROTOCOL_ERROR" will be displayed in the console.

HTTP/3

HTTP/3 is the successor to HTTP/2. As of September 2020, all major browsers have experimental support for HTTP/3 and some CDNs support it. Performance is the primary benefit of HTTP/3 over HTTP/2. Specifically, HTTP/3 eliminates head-of-line blocking at the connection level and reduces connection setup time.

Elimination of head-of-line blocking

HTTP/2 introduced multiplexing, a feature that allows a single connection to be used to transmit multiple streams of data simultaneously. However, with HTTP/2, a single dropped packet blocks all streams on a connection (a phenomena known as a head-of-line blocking). With HTTP/3, a dropped packet only blocks a single stream. This improvement is largely the result of HTTP/3 using UDP (HTTP/3 uses UDP via QUIC) rather than TCP. This makes HTTP/3 particularly useful for data transfer over congested or lossy networks.

Reduced connection setup time

HTTP/3 uses TLS 1.3 and therefore shares its performance benefits: establishing a new connection only requires a single round-trip and resuming an existing connection does not require any roundtrips.

HTTP/3 will have the biggest impact on users on poor network connections: not only because HTTP/3 handles packet loss better than its predecessors, but also because the absolute time savings resulting from a 0-RTT or 1-RTT connection setup will be greater on networks with high latency.

Image optimization

CDN image optimization services typically focus on image optimizations that can be applied automatically in order to reduce image transfer size. For example: stripping EXIF data, applying lossless compression, and converting images to newer file formats (for example, WebP). Images make up ~50% of the transfer bytes on the median web page, so optimizing images can significantly reduce page size.

Minification

Minification removes unnecessary characters from JavaScript, CSS, and HTML. It's preferable to do minification at the origin server, rather than the CDN. Site owners have more context about the code to be minified and therefore can often use more aggressive minification techniques than those employed by CDNs. However, if minifying code at the origin is not an option, minification by the CDN is a good alternative.

Conclusion

- Use a CDN: CDNs deliver resources quickly, reduce load on the origin server, and are helpful for dealing with traffic spikes.

- Cache content as aggressively as possible: Both static and dynamic content can and should be cached - albeit for varying durations. Periodically audit your site to make sure that you are optimally cacheing content.

- Enable CDN performance features: Features like Brotli, TLS 1.3, HTTP/2, and HTTP/3 further improve performance.